Introduction

The main goal of this documentation is to describe how to program the modules of the MCXA153 microcontroller directly through its registers, instead of using driver functions. This is done by providing a basic example for each module and an assignment on top of that example. The hardware required for these assignments is an FRDM-MCXA153 development board.

There are also additional assignments to verify the knowledge acquired. These are marked with Assignment. These extra assignments require additional hardware, which is conveniently available on a dedicated Shield V3.

The content of this site can also be downloaded as a single PDF as follows:

- Add print_page.html at the end of the URL

- CTRL+P

- Save as PDF

Prior knowledge and skills

Before starting with these example projects, it is expected that you have the following knowledge and skills:

- Know how to represent numbers in different numbering systems, such as decimal, binary, and hexadecimal.

- Can program in C at the beginners level.

- Know the bitwise operators and what they are used for.

- Know what a register is.

Disclaimer

This content is provided for education and demonstration purpose.

Static documents

This content uses static documents downloaded from several sources. The reason for this is the ability to directly reference paragraphs and pages within these documents, which makes it more convenient to find relevant information. The following documents were downloaded and are part of this content:

- Arm® v8-M Architecture Reference Manual - DDI0553B.x ID15122023

- FRDM-MCXA153 Board User Manual - Rev. 2.0 — 12 February 2025

- FRDM-MCXA153 Schematic diagrams - Rev A1, 28-Aug-2023

- MCX A153, A152, A143, A142 Reference Manual - Rev. 5, 08/2024

- MCXA153, A152, A143, A142 Data Sheet - Rev. 3 — 01/2024

- P3T1755 Product data sheet - Rev. 1.1 — 4 January 2023

- ARM® Cortex®-M for Beginners - White paper - March 2017

Note. You are encouraged to always check if there are new versions of these documents.

KiCad shield template

Myrddin has created a FRDM-MCXA153 shield template for KiCad that fit's both the Arduino headers and the mikroBUS headers at the same time. The shield template is available here.

Contact

This content is part of the microcontroller courses offered by HAN Embedded Systems Engineering.

Have any comments or suggestions? Please let me know by sending me an email.

Hugo Arends

Arnhem - December 2025

Getting Started with VS Code

Resources: ese_general_examples\basics\getting_started

Rather use MCUXpresso-IDE? Check this getting started instead!

Hardware

The NXP FRDM-MCXA153 development board is used in this course.

A board overview, product details, documentation and other resources is provided on the NXP website. A board can purchased from ARLE, the NXP website or other electronics suppliers.

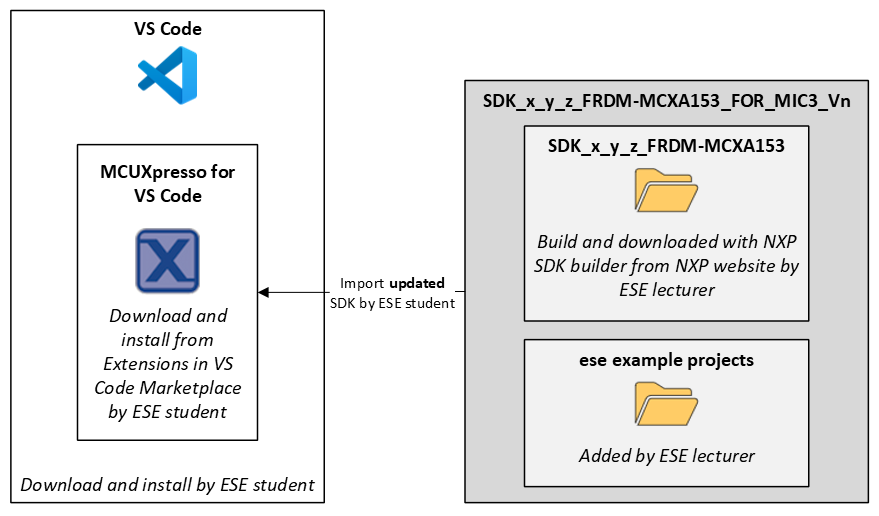

SDE overview

The following diagram shows the tools and dependencies used in the Software Development Environment. A detailed description of where to download and how to configure these tools is given in the rest of this document.

Download and install VS Code

Download and install the latest version of VS Code for your operating system.

Download and install extensions

Download and install the MCUXpresso for VS Code extension.

- Start VS Code

- Install the MCUXpresso for VS Code extension: MCUXpresso for VS Code

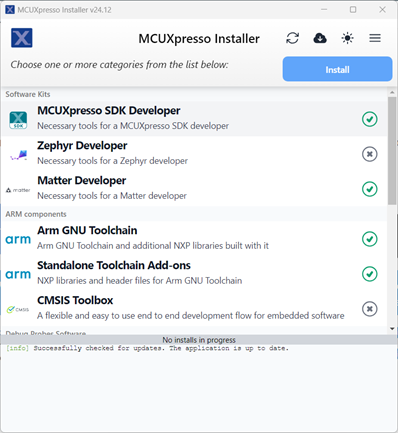

Download and install MCUXpresso for VS Code components

After installing the MCUXpresso for VS Code extension, you should be prompted to start the MCUXpresso Installer. If not, click Open MCUXpresso Installer from the Quickstart panel in the MCUXpresso for VS Code extension.

The MCUXpresso Installer looks like this:

- In this installer, select (at least) the following options:

- MCUXpresso SDK Developer

- ARM GNU Toolchain

- Standalone Toolchain Add-ons

- LinkServer

- SEGGER J-Link

- Click Install

- Close the installer when the installation is finished

Download SDK

The Software Development Kit (SDK) contains source files, project configuration files, documentation, example projects, etc. to help users get started. The updated SDK is available for download as a ZIP archive.

- Download the file SDK_x_y_z_FRDM-MCXA153_FOR_MIC3_Vn.zip from Brightspace.

Note. If you would like to generate your own SDK, without ESE examples, use the SDK builder for the FRDM-MCXA153

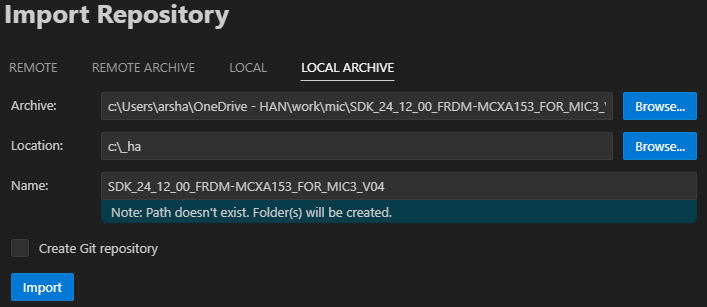

Import SDK in MCUXpresso for VS Code

The downloaded SDK must be imported in MCUXpresso for VS Code.

- Start VS Code

- Select the MCUXpresso for VS Code extension

- Click Import Repository

- Click LOCAL ARCHIVE

- Archive: select the dowloaded SDK

- Location: any location will do, but the path should be as short as possible!

- Name: leave default

- Create Git repository: not checked

The result should look similar to this:

- Click Import

- Wait for the import to finish

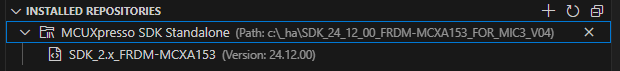

After a successful import, the installed SDK is added to the Installed repositories view. For example:

Note. An SDK can be removed by a right-mouse click on the SDK and selecting the appropriate option from the context menu that pops-up.

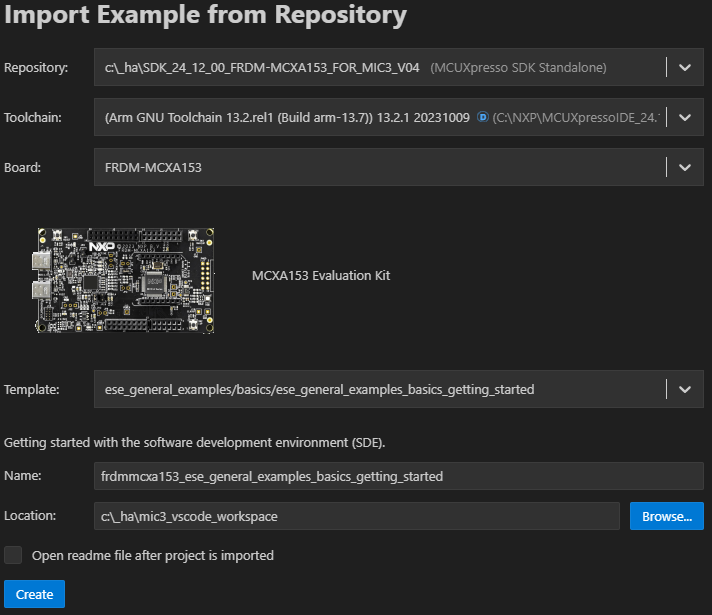

Import example project in MCUXpresso for VS Code

Import example projects from the SDK in MCUXpresso for VS Code.

- Start VS Code

- Select the MCUXpresso for VS Code extension

- Click Import Example from Repository

- Repository: select the downloaded SDK

- Toolchain: ARM GNU Toolchain (as installed during with MCUXpresso Installer)

- Board: FRDM-MCXA153

- Template: ese_general_examples/basics/ese_general_examples_basics_getting_started

- Name: leave default

- Location: any location will do, but the path should be as short as possible!

The result should look similar to this:

- Click Create

- Wait for the import to finish

MCU-Link firmware update (optional)

The FRDM-MCXA153 board comes with an MCU-Link debug probe. Out of the box, the CMSIS-DAP firmware is installed. Changing the MCU-Link to J-Link firmware is described here.

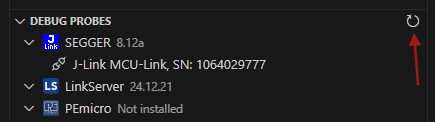

Check board connection

Check if the board is recognized by MCUXpresso for VS Code.

- Connect the FRDM-MCXA153 board to the computer with a USB cable (J15 - MCU-Link)

- Check the Debug probes view to make sure the board is detected. If not, click the Refresh debug probes icon

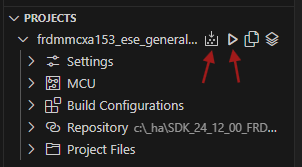

Build and run the Getting Started application

The imported project is visible in the Projects view in the MCUXpresso for VS Code extension.

Build and run the project.

- Click the Build icon

- Check the Terminal window for the build to finish successfully

- Click the debug icon

- Wait for the debugger to start

- Click Run, the green LED starts blinking

Note: If you run into build issues, chances are that the path to the project is too long and/or the path contains characters that are not supported by the toolchain (such as hyphens). If so, move the project and the SDK to a location with a shorter path and/or remove unsupported characters from the path.

CMSIS

Resources: none

Goal

To understand what the CMSIS is and how bits are manipulated in registers in C by using CMSIS.

Required hardware

- None

Introduction

This course aims at teaching how to program the modules of the microcontroller directly through its registers, instead of using driver functions. This will be achieved by making use of the Common Microcontroller Software Interface Standard (CMSIS). One subject of this standard is the naming convention for accessing modules. Microcontroller vendors offer CMSIS compliant header and source files that can be added to a project, which is often automated when creating a new project in the SDE of choice. The benefit of using this naming convention is that accessing registers of peripherals in C is done by simple statements. Most microcontroller vendors use names that are also used in their reference manual and/or datasheet.

The CMSIS naming convention for accessing modules is:

MODULE->REGISTER

For example, setting the CTRL register in the SysTick module to zero is done as follows:

SysTick->CTRL = 0x00000000;

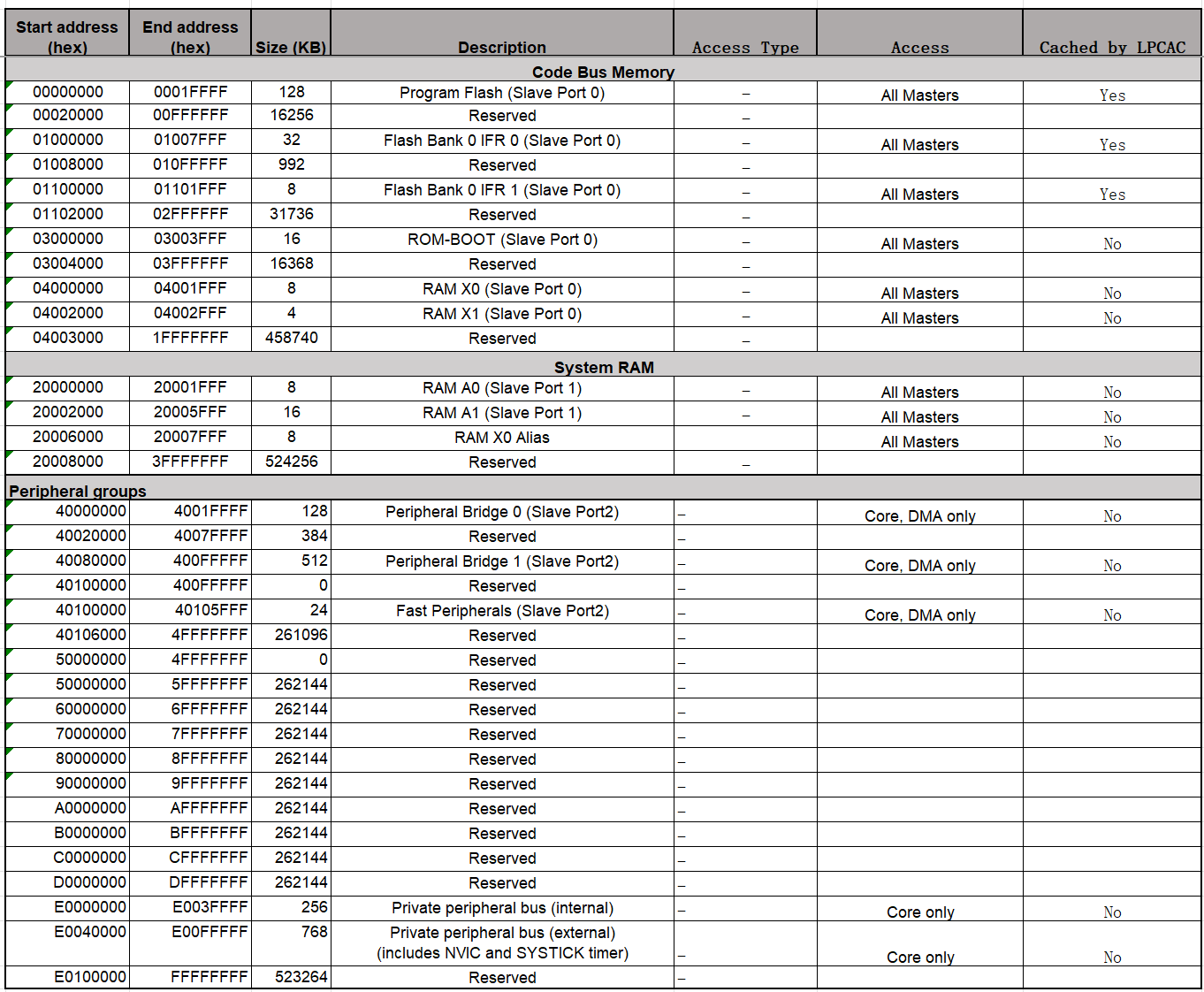

Memory mapped IO

All registers in an ARM Cortex-M microcontroller are memory mapped. This means that every registers is located at a 32-bit address. For example, the SySTick->CTRL register in the MCXA153 microcontroller is located at address 0xE000E010. Writing a 32-bit number to this 32-bit address in C can be done as follows:

*((volatile uint32_t *)(0xE000E010)) = 0x00000000;

This is both unreadable and not portable.

Within the SysTick module, there are a total of four 32-bit registers. These registers are called:

- CTRL - Control and Status register

- LOAD - Reload value register

- VAL - Current value register

- CALIB - Calibration register

These register are conveniently grouped in memory. CMSIS takes advantage of the fact that a struct in C is a way to group variables. The registers memory layout of the SysTick module can therefore be represented as a struct:

typedef struct

{

volatile uint32_t CTRL; /*!< Offset: 0x000 (R/W) SysTick Control and Status Register */

volatile uint32_t LOAD; /*!< Offset: 0x004 (R/W) SysTick Reload Value Register */

volatile uint32_t VAL; /*!< Offset: 0x008 (R/W) SysTick Current Value Register */

volatile const uint32_t CALIB; /*!< Offset: 0x00C (R/ ) SysTick Calibration Register */

} SysTick_Type;

The base address in memory of this struct will be the address of the first field in the struct, being the CTRL register in this example. And the address of the CTRL register is known, because this is described in the reference manual (or in this case the ARMv8-M documentation, because this is a core register). A more meaningful name for the base address of the module is defined as follows:

#define SysTick ((SysTick_Type *) 0xE000E010 )

This means: SysTick is a pointer pointing to a SysTick_Type struct at address 0xE000E010.

Accessing one of the fields can thus be achieved by using the pointer to a struct

dereference operator: ->

For example:

SysTick->CTRL = 0x00000000;

Cortex-M microcontroller vendors offer comprehensive header files for their devices with CMSIS compliant defines for all the modules and registers.

Bit manipulation

Bits in register are manipulated with the C bitwise operators as follows:

// Assignment: assign a value to all bits in a register

MODULE->REGISTER = (0x00010001);

// Bitwise-or: set bits in a register and leave all others unchanged

MODULE->REGISTER |= (0x00010001);

// Bitwise-and: clear bits in a register and leave all others unchanged

MODULE->REGISTER &= ~(0x00010001);

// Bitwise ex-or: toggle bits in a register and leave all others unchanged

MODULE->REGISTER ^= (0x00010001);

Bit field masks

Instead of using magic numbers (such as 0x00010001 in the example above), CMSIS also provides a convention for accessing bit fields in a register. The convention describes the following three defines for each bit field:

// A 32-bit mask with logic 1s at every location of the bit field

MODULE_REGISTER_BITFIELD_MASK

// The bit position of the LSB of the bit field

MODULE_REGISTER_BITFIELD_SHIFT

// A macro to shift the number x to the bit fields location in the register.

// The macro also makes sure that if an invalid number is written (i.e. too

// large for the bit field), all bits outside the bit field boundary are

// set to logic 0.

MODULE_REGISTER_BITFIELD(x)

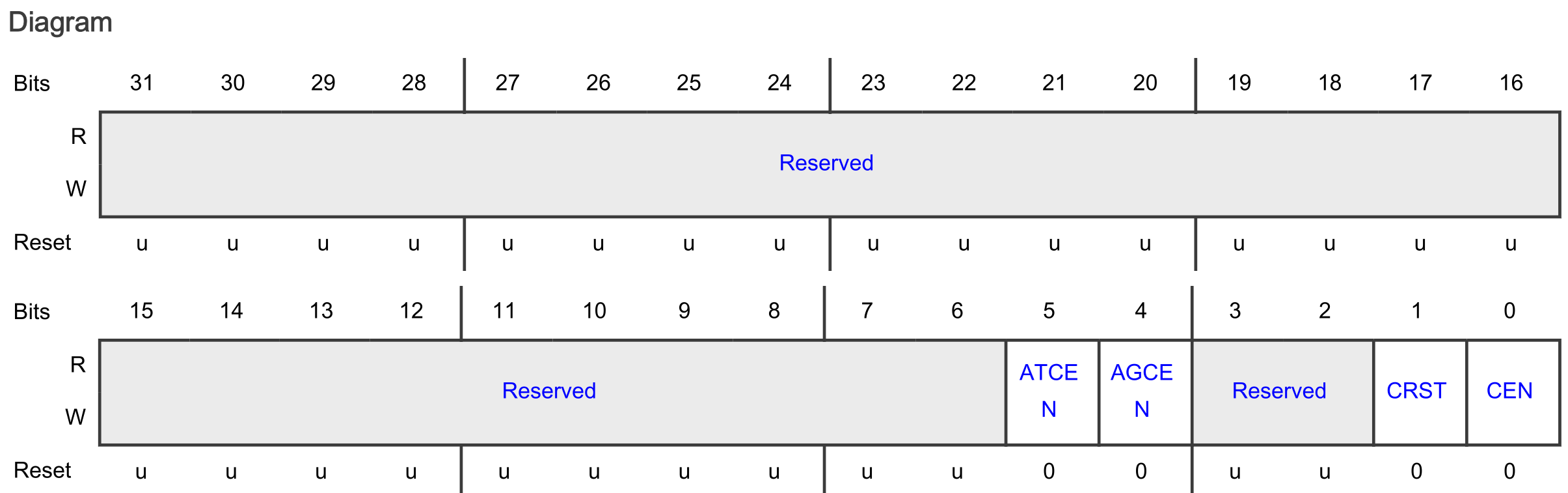

As an example, let's have a look at the TCR register. It's description diagram is taken from the reference manual.

According to the convention, the following defines are available for the CEN bit field in this TCR register:

#define CTIMER_TCR_CEN_MASK (0x1U)

#define CTIMER_TCR_CEN_SHIFT (0U)

#define CTIMER_TCR_CEN(x) (((uint32_t)(((uint32_t)(x)) << CTIMER_TCR_CEN_SHIFT)) & CTIMER_TCR_CEN_MASK)

These defines can for example be used as follows.

// Set the CEN bit field in the TCR register in the CTIMER1 module and leave

// all other bits unchanged. Notice that all three instructions have the same

// result!

CTIMER1->TCR |= CTIMER_TCR_CEN(1);

CTIMER1->TCR |= (1 << CTIMER_TCR_CEN_SHIFT);

CTIMER1->TCR |= CTIMER_TCR_CEN_MASK;

// Reset the CEN bit field in the TCR register in the CTIMER1 module and leave

// all other bits unchanged. Notice that all three instructions have the same

// result!

CTIMER1->TCR &= ~(CTIMER_TCR_CEN(1));

CTIMER1->TCR &= ~(1 << CTIMER_TCR_CEN_SHIFT);

CTIMER1->TCR &= ~(CTIMER_TCR_CEN_MASK);

As a reference, here are several examples for other registers and bits in the MCXA153 microcontroller.

// Set the PCS bit field in the PSR register of LPTMR0 module to 3 and reset

// all others!

LPTMR0->PSR = LPTMR_PSR_PCS(0b11);

// Set the LK bit field in PCR 0 register of PORT3 and reset all other bits!

PORT3->PCR[0] = PORT_PCR_LK(1);

// Check if the TDRE bit field in the STAT register of the LPUART0 module is

// not equal to zero.

if((LPUART0->STAT & LPUART_STAT_TDRE_MASK) != 0)

// Check if the BBF bit field or the MBF bit field in the MSR register of the

// LPI2C module is not equal to zero.

while((LPI2C0->MSR & (LPI2C_MSR_BBF_MASK | LPI2C_MSR_MBF_MASK)) != 0)

Extra

Curious how the three defines for bit field masks evaluate at compile time? Read this!

GPIO output

Resources: ese_driver_examples\gpio\output

Goal

Know how to initialize and control a digital output pin with the GPIO module.

RGB LED - Which pin to use?

The FRDM-MCXA153 board contains an RGB LED that can be controlled by the user. Before being able to control the RGB LED, the physical connection on the FRDM-MCXA153 board must be verified. Checking the board schematic page 7 shows the following pin connections:

- LED_RED: PORT3 pin 12 (P3_12)

- LED_GREEN: PORT3 pin 13 (P3_13)

- LED_BLUE: PORT3 pin 0 (P3_0)

PORTn modules provide support for pin control functions. This microcontroller features four PORT modules: PORT0 to PORT3. Each PORT module is capable of controlling 32 pins (provided that a pin is available on the particular microcontroller package).

Initialization

GPIO modules can be used to control the logic state of a microcontroller pin. However, a pin must first be configured for the GPIO function. This is done in the PORT module. Using P3_13 as an example, it takes the following steps to configure the pin for GPIO:

- Enable the PORT3 and GPIO3 modules in the Module Reset and Clock Control (MRCC) module.

- Initialize P3_13 for GPIO function in the PORT3 module.

- Initialize P3_13 for output function in the GPIO3 module.

These steps are explained in more detail in the following sections.

1. Enable the PORT3 and GPIO3 modules

The MRCC module must be used to enable other modules, such as PORT3 and GPIO3. How this is done is described in the reference manual paragraph 14.3.

// Before a module can be used, its clocks must be enabled (CC != 00) and it

// must be released from reset (MRCC_GLB_RST [peripherals name] = 1). If a

// module is not released from reset (MRCC_GLB_RST [peripherals name] = 0),

// an attempt to access a register within that module is terminated with a

// bus error.

This description translates to the following C instructions for the GPIO3 and PORT3 modules:

// Enable modules and leave others unchanged

// GPIO3: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

// PORT3: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC1 |= MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC1_GPIO3(1);

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC1 |= MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC1_PORT3(1);

// Release modules from reset and leave others unchanged

// GPIO3: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

// PORT3: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST1 |= MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST1_GPIO3(1);

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST1 |= MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST1_PORT3(1);

The use of defines such as MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC1_PORT3(1) for bit fields makes the code very readable and portable. The naming convention for such defines is as follows:

MODULE_REGISTER_BITFIELD(x)

Want to know how this define works and what other defines are available? Read this!

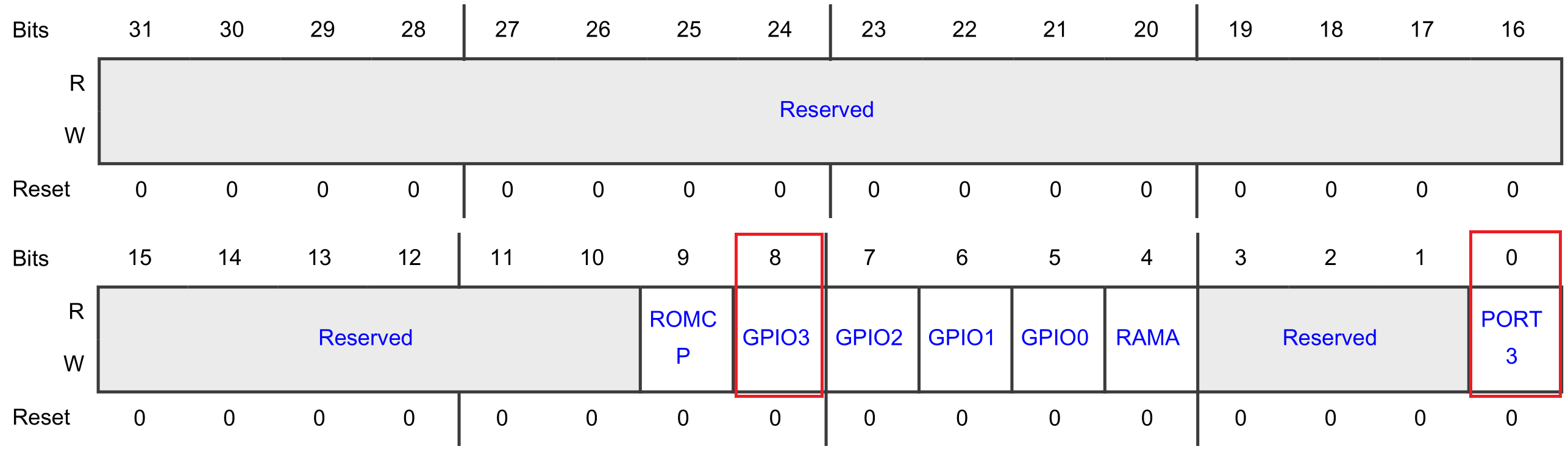

These instructions set bit 0 and bit 8, because according the MRCC_GLB_CC1 and MRCC_GLB_RST register diagrams:

- PORT3 is bit position 0

- GPIO3 is bit position 8

So, alternatively, the following instructions could have been used:

// Enable modules and leave others unchanged

// GPIO3: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

// PORT3: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC1 |= (1<<0);

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC1 |= (1<<8);

// Release modules from reset and leave others unchanged

// GPIO3: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

// PORT3: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST1 |= (1<<0);

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST1 |= (1<<8);

2. Initialize P3_13 for GPIO function

The PORT module must be used to configure the function for a pin. How this is done is described in the reference manual paragraph 11.4.

// 1. Initialize the pin functions:

// - Initialize single pin functions by writing appropriate values to

// PCRn

// - Initialize multiple pins (up to 16) with the same configuration by

// writing appropriate values to Global Pin Control Low (GPCLR) or

// Global Pin Control High (GPCHR).

// 2. Lock the configuration for a given pin, by writing 1 to PCRn [LK], so

// that it cannot be changed until the next reset.

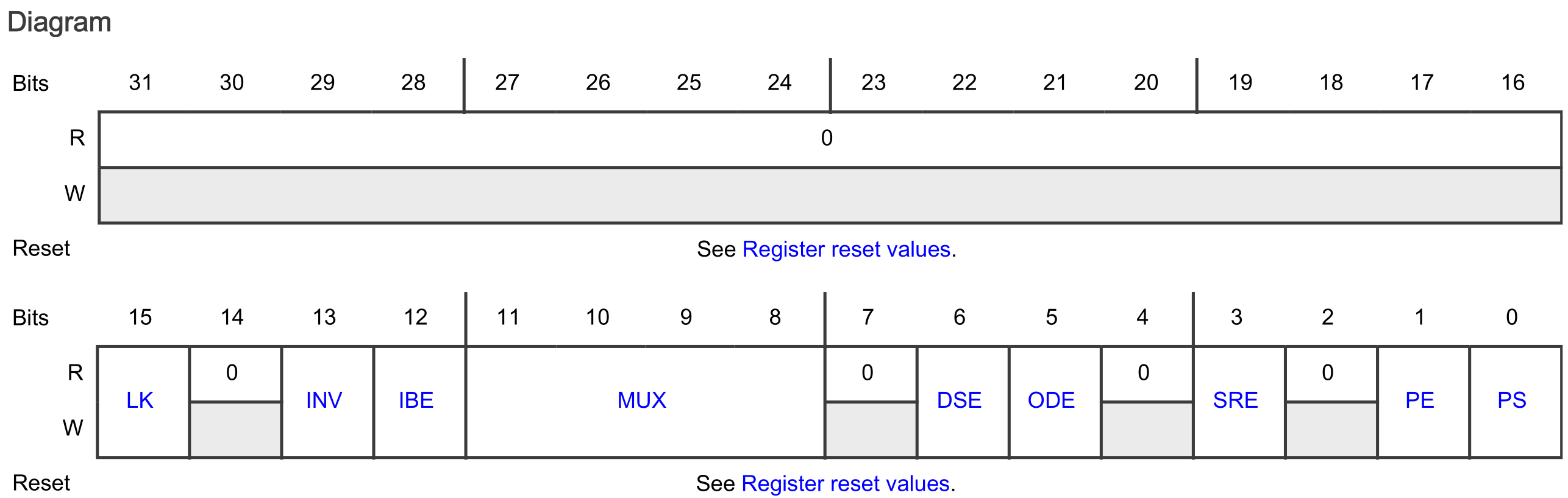

There is a PCR register for each and every pin. The reference manual describes the PCR registers in detail, for example PCR10-PCR13:

Each PORT contains up to 32 PCR registers. These registers all have the same layout, and are organized in an array. The PCR register for P3_13 is addressed as follows:

PORT3->PCR[13]

This register is used as follows for pin P3_13 to:

- Set the LK bit field to [1]: Lock this PCR

-

Set the MUX bit field to [0000]: alternative 0 (GPIO)

Refer to the reference manual paragraph 11.6, find Pin control a (PCR10 - PCR13), find the MUX bit-field description and make sure to understand why the alternative is set to 0 for GPIO.

-

Set all other bit fields to their reset value logic 0

// 1. & 2.

//

// Configure P3_13

// LK : [1] = Locks this PCR

// INV: [0] = Does not invert

// IBE: [0] = Disables

// MUX: [0000] = Alternative 0 (GPIO)

// DSE: [0] = low drive strength is configured on the corresponding pin,

// if the pin is configured as a digital output

// ODE: [0] = Disables

// SRE: [0] = Fast

// PE: [0] = Disables

// PS: [0] = n.a.

PORT3->PCR[13] = 0x00008000;

3. Initialize P3_13 for output function

Refer to the reference manual paragraph 12.5. The following description is provided to initialize a pin for the output function:

// 1. Initialize the GPIO pins for the output function:

// a. Configure the output logic value for each pin by using Port Data

// Output (PDOR).

// b. Configure the direction for each pin by using Port Data Direction

// (PDDR).

// 2. Interrupt function not used.

Note: The interrupt function is not used in this example.

This description tells that there is a PDOR and PDDR register for the GPIO pins. For P3_13, these registers are addressed as follows:

GPIO3->PDOR

GPIO3->PDDR

Manipulating the 13th bit in these registers, manipulates pin P3_13. The following C instructions can be used, according to the description, to initialize P3_13 as an output pin:

// 1. a.

//

// PDO13: [1] = Logic level 1 – LED green off

GPIO3->PDOR |= (1<<13);

// 1. b.

//

// PDD13: [1] = Output

GPIO3->PDDR |= (1<<13);

Pin toggling

After initialization the pin can be toggled by using the PDOR register in the GPIO peripheral. Setting a bit in the PDOR can also be done by using the PSOR register. For resetting a bit in the PDOR register, the PCOR register can be used.

The following while-loop uses the PSOR and PCOR registers to create a blinking green LED:

while(1)

{

// LED green off

// Write logic 1 to bit 13 in the GPIO3 PSOR register so the

// corresponding bit in PDOR becomes 1

GPIO3->PSOR = (1<<13);

// Delay

for(volatile int i=0; i<1000000; i++)

{}

// LED green on

// Write logic 1 to bit 13 in the GPIO3 PCOR register so the

// corresponding bit in PDOR becomes 0

GPIO3->PCOR = (1<<13);

// Delay

for(volatile int i=0; i<1000000; i++)

{}

}

As mentioned, the same blinking functionality could have been achieved by using the PDOR register of PORT3. For example:

// Write logic 1 to PDOR bit 13

GPIO3->PDOR |= (1<<13);

// Write logic 0 to PDOR bit 13

GPIO3->PDOR &= ~(1<<13);

By using the PSOR and PCOR registers, there is no need to read the content of the PDOR register for updating a single bit. If the bitwise operators are used, there are three actions involved: Read-Modify-Write. Hence, this is not not an atomic action, and can thus be interrupted. Writing to the PSOR or PCOR register is an atomic action.

Another alternative for toggling a pin is by using the PTOR register. For example:

// Toggle the pin

GPIO3->PTOR = (1<<13);

Assignment

- Update the application so the red RGB LED blinks, instead of the green RGB LED.

- Update the application and initialize all the pins connected to the RGB LED as GPIO output.

- Update the while-loop to show the following sequence:

red -> green -> blue -> off -> red -> green -> blue -> off -> etc.

Extra

Create an LED chaser.

- Use a six LED breakout board, such as

Alternatively, use six LEDs with suitable series resistors. Make sure the anode of the LED is connected to the microcontroller pin and the cathode to GND. Do not forget to add the series resistors.

- Connect the LEDs and the FRDM-MCXA153 board as follows:

| FRDM-MCXA153 | LED |

|---|---|

| GND | GND |

| P2_12 | D1 |

| P2_16 | D2 |

| P2_13 | D3 |

| P2_6 | D4 |

| P3_14 | D5 |

| P3_15 | D6 |

- In the file gpio_output.c correctly configure the pins so they can be used as GPIO output pins. Notice that PORT2 is also used.

TIP: There are two registers for MRCC_GLB_CC: MRCC_GLB_CC0 and MRCC_GLB_CC1. The same applies to MRCC_GLB_RST: MRCC_GLB_RST0 and MRCC_GLB_RST1. Refer to the reference manual to locate these registers and carefully verify where each module (PORT2, GPIO2, PORT3, and GPIO3) is enabled.

- After successfully configuring the pins, create an LED chaser in

main.c.

TIP: So far, delays have been created by for-loops. If you are curious about how to use a timer for that, you might want to take a look at the SysTick timer example. You can also import this example in the IDE from ese_driver_examples\systick\match_interrupt.

GPIO Input - polling

Resources: ese_driver_examples\gpio\input_polling

Goal

Know how to initialize and read a digital input pin by polling a bit in the GPIO module.

Switches - Which pin to use?

The FRDM-MCXA153 board contains three switches. One of these switches is SW3, which is used in this example. However, before being able to read the logic state of SW3, the physical connection on the FRDM-MCXA153 board must be verified. Referring to the board schematic page 7, it shows that PORT1 pin 7 (P1_7) is connected to switch SW3 (a.k.a. WAKEUP).

The schematic also shows that an external pullup resistor is connected to SW3. So, pressing SW3 connects it to GND, reading logic 0.

Initialization

Similar to GPIO output pins, the GPIO modules must be used to read the logic state of a microcontroller pin. However, a pin must first be configured for the GPIO function. Using P1_7 as an example, it takes the following steps to configure the pin for GPIO:

- Enable the PORT1 and GPIO1 modules in the MRCC module.

- Initialize P1_7 for GPIO function in the PORT1 module.

These steps are explained in more detail in the following sections. No additional action is needed, because the default direction of a pin is input.

1. Enable the PORT1 and GPIO1 modules

The MRCC module must be used to enable other modules, such as PORT1 and GPIO1. How this is done is described in the reference manual paragraph 14.3.

// Before a module can be used, its clocks must be enabled (CC != 00) and it

// must be released from reset (MRCC_GLB_RST [peripherals name] = 1). If a

// module is not released from reset (MRCC_GLB_RST [peripherals name] = 0),

// an attempt to access a register within that module is terminated with a

// bus error.

This description translates to the following C instructions:

// Enable modules and leave others unchanged

// PORT1: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

// GPIO1: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC0_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC0_PORT1(1);

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC1_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC1_GPIO1(1);

// Release modules from reset and leave others unchanged

// PORT1: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

// GPIO1: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST0_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST0_PORT1(1);

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST1_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST1_GPIO1(1);

2. Initialize P1_7 for GPIO function

The PORT module must be used to configure the function for a pin. How this is done is described in the reference manual paragraph 11.4.

// 1. Initialize the pin functions:

// - Initialize single pin functions by writing appropriate values to

// PCRn

// - Initialize multiple pins (up to 16) with the same configuration by

// writing appropriate values to Global Pin Control Low (GPCLR) or

// Global Pin Control High (GPCHR).

// 2. Lock the configuration for a given pin, by writing 1 to PCRn [LK], so

// that it cannot be changed until the next reset.

There is a PCR register for each and every pin. The reference manual describes the PCR registers in detail. The PCR register for P1_7 is addressed as follows:

PORT1->PCR[7]

This register is used as follows for pin P1_7 to:

- Set the LK bit field to [1]: Lock this PCR.

- Set the IBE bit field to [1]: Input Buffer Enable.

- Set the MUX bit field to [0000]: alternative 0 (GPIO).

- Set all other bit fields to their reset value logic 0.

// 1. & 2.

//

// Configure pins

// LK : [1] = Locks this PCR

// INV: [0] = Does not invert

// IBE: [1] = Digital Input Buffer Enable, otherwise pin is used for analog

// functions

// MUX: [0000] = Alternative 0 (GPIO)

// DSE: [0] = low drive strength is configured on the corresponding pin,

// if the pin is configured as a digital output

// ODE: [0] = Disables

// SRE: [0] = Fast

// PE: [0] = Disables

// PS: [0] = n.a.

PORT1->PCR[7] = PORT_PCR_LK(1) | PORT_PCR_IBE(1) | PORT_PCR_MUX(0);

Reading the pin logic state

After initialization the pin logic state can be read from PDIR register in the GPIO peripheral. For example:

while(1)

{

// SW3 pressed?

if((GPIO1->PDIR & (1<<7)) == 0)

{

// Green LED on

GPIO3->PCOR = (1<<13);

}

else

{

// Green LED off

GPIO3->PSOR = (1<<13);

}

}

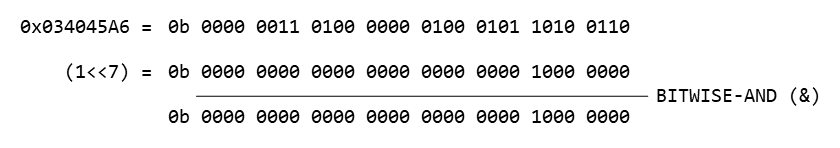

Suppose the value of the GPIO1->PDIR register is 0x034045A6 and the if-statement is executed. The question is: Will the green LED be on or off?

The answer to this questions depends on the value of the register (which in turn depends on the connected hardware) and the mask.

The result of the bitwise-and operator is not equal to zero, so the expression in the if-statement is false. The green LED will be off.

Assignment

- Also initialize the pin connected to SW2 as GPIO input pin.

- Update main as follows:

- If SW3 is pressed the green LED switches on

- If SW2 is pressed the green LED switches off

Core clock

Resources: none

The core clock runs by default at 48 MHz.

Goal

Know why the default core clock frequency of the MCXA153 is 48 MHz.

Required hardware

- None

Clocking

So far, the following for-loop has been used to create a delay:

// Delay

for(volatile int i=0; i<1000000; i++)

{}

This gave a nice visual effect, because the blinking of the LED was not too slow nor too fast. A more precise timing, however, is preferred, so let's first find out at which frequency the MCXA153 microcontroller is executing instructions.

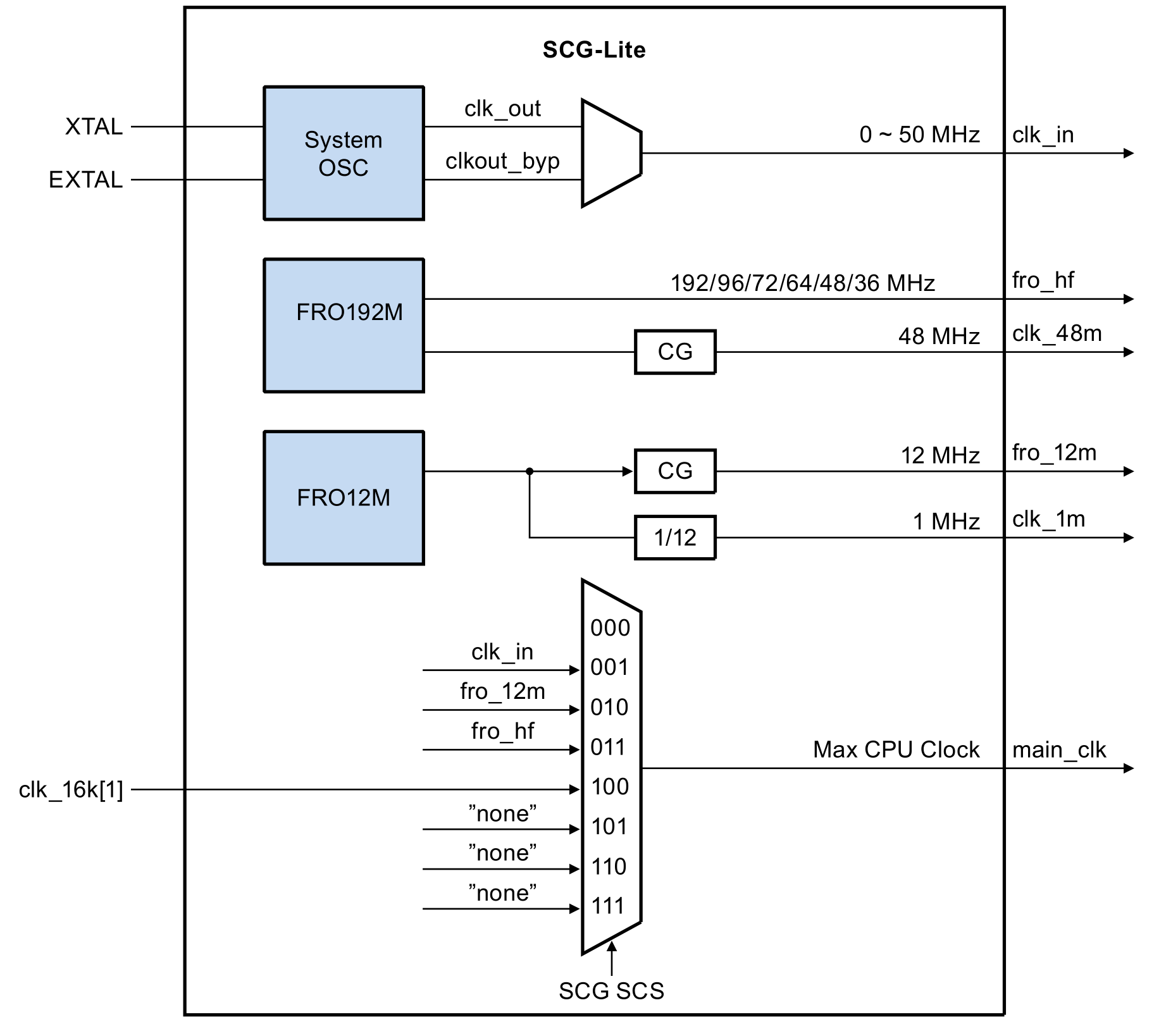

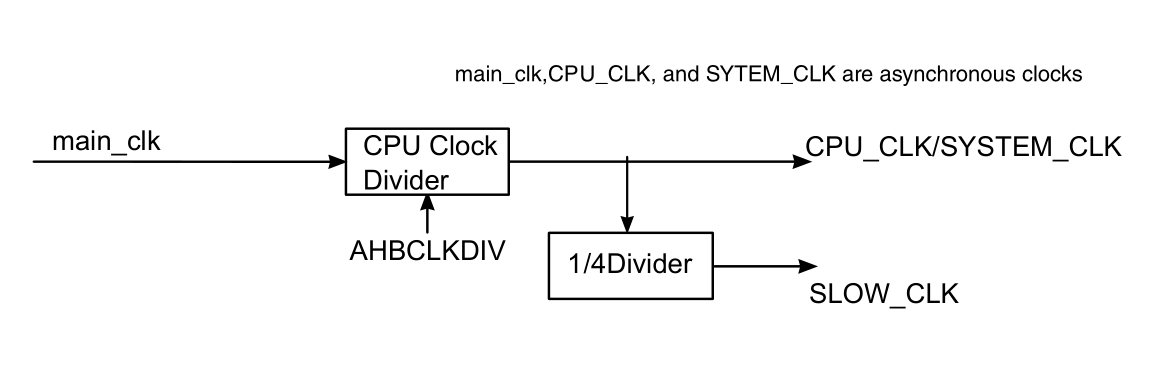

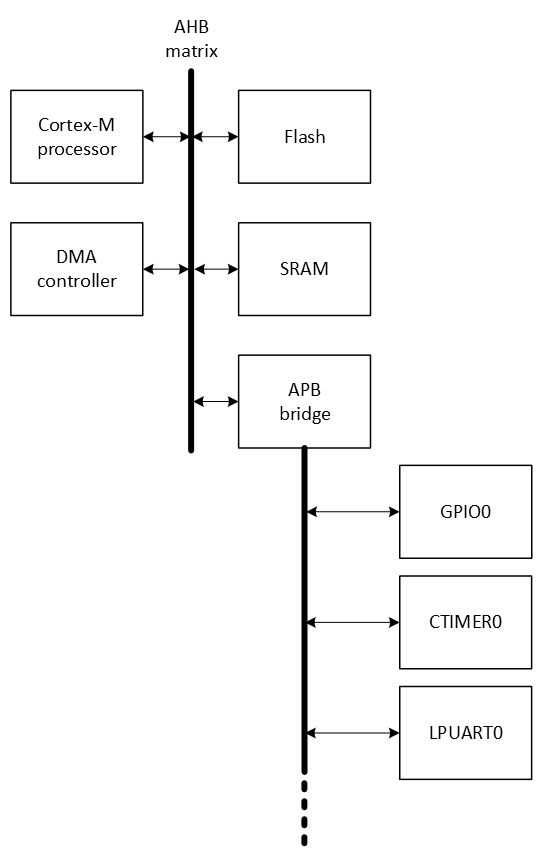

The clocking options are depicted in the following figure in chapter 21 of the reference manual.

It shows that:

- There is a clocking module called System OSC. OSC means OSCillator. This module derives a clock frequency from an externally connect XTAL oscillator. XTAL means crystal.

- There are two internal clocking modules, called FRO192M and FRO12M. FRO means Free Running Oscillator. M means MHz.

- CG means Clock Gating. This is a means to disable clock signals in order to save power. CG is enabled/disabled by writing bits in specific registers.

- The main_clk can be selected from eight inputs, however, only four are implemented. The main_clk is selected in the SCG module by the SCS bits (located in the CSR register).

The default value (after a reset) of the SCS bits in the SCG->CSR register is described in chapter 22 of the reference manual. The value of these bits is 0b011, which means the option FIRC is selected.

SCS: Returns the currently configured clock source generating the system clock.

000b - Reserved

001b - SOSC

010b - SIRC

011b - FIRC

100b - ROSC

101b-111b - Reserved

And furthermore, referring to section 22.1.3 Clock decoder ring, it shows how the clock name sources in the SCG chapter translate to names throughout the rest of the reference manual:

| SCG chapter name | Reference manual name |

|---|---|

| SOSC | clk_in |

| SIRC | fro_12m |

| FIRC | fro_hf |

| ROSC | clk_16k[1] |

So by default, the fro_hf clock is selected for the main_clk. However, the image shows that this can be one of the following frequencies: 192/96/72/64/48/36 MHz. Paragraph 21.2 states that the fro_hf default frequency is 48 MHz.

Finally, the main_clk is used to clock the CPU and rest of the system. The CPU Clock Divider, as shown in the following figure in chapter 21 of the reference manual, divides this clock. It shows that the AHBCLKDIV register is used to set the divider value.

The AHBCLKDIV register in chapter 14 of the reference manual shows that the default (reset) value of the DIV bits:

Clock divider value = (DIV + 1) = 0b00000000 + 1 = 1

So by default, the main_clk is divided by 1.

Conclusion

By default the CPU core clock runs at 48 MHz.

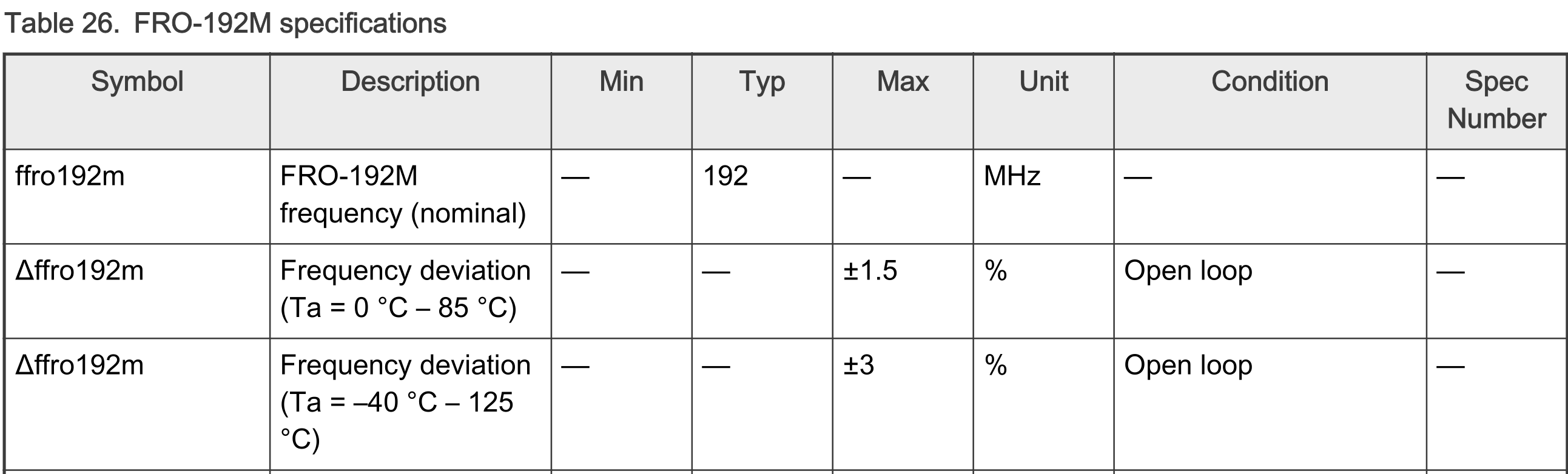

Or is it? Please be aware of the fact that the clock signal generated by the FRO modules have a deviation margin. This margin is specified in the datasheet. In timing critical applications, this deviation might be a problem. In such applications, an external oscillator with better precision can be connected to the XTAL and EXTAL pins.

NVIC

Resources: none

Goal

To understand how the NVIC handles interrupts and use CMSIS to configure the NVIC.

Required hardware

- None

Introduction

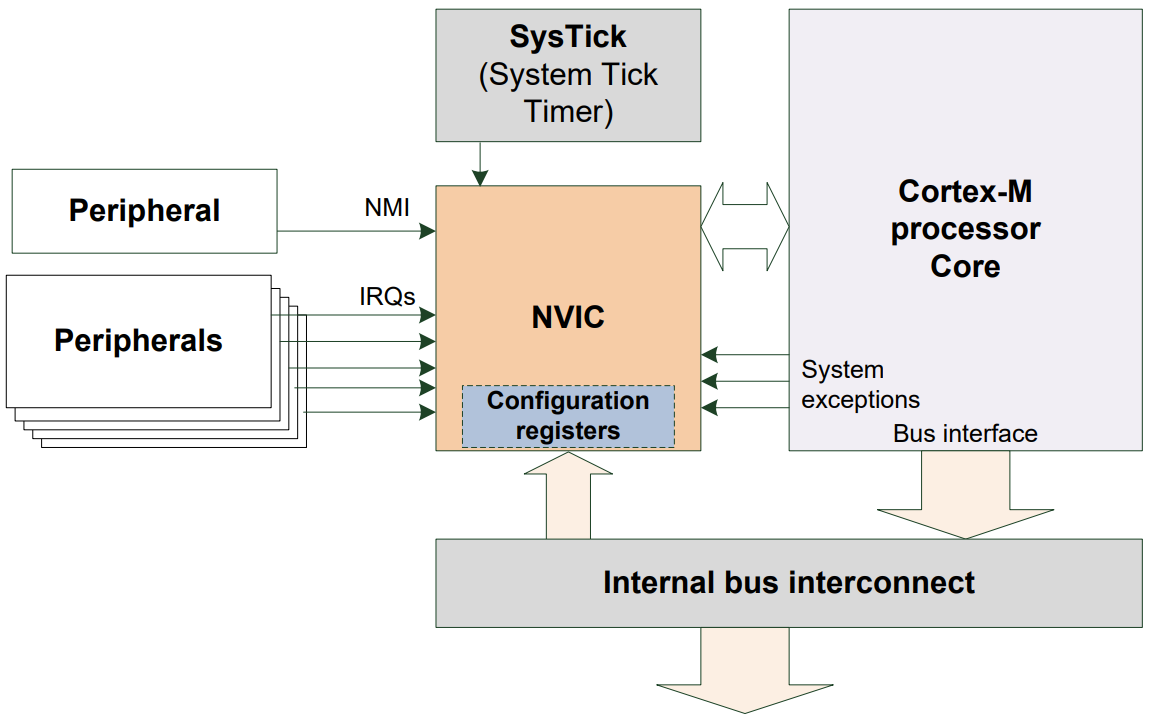

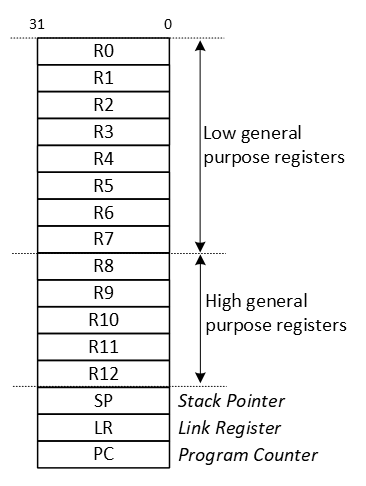

The Nested Vectored Interrupt Controller (NVIC) handles the priority management and masking of interrupts and exceptions. The NVIC is closely coupled with the core as depicted and described in this white paper:

Each interrupt can be in one of the following states:

- Inactive

The interrupt is not active and not pending

- Active

Indicates that this interrupt is being serviced

- Pending

Indicates that an interrupt is waiting to be serviced.

- Active and pending at the same time

The interrupt is being serviced by the core and there is a pending exception from the same source

Nesting

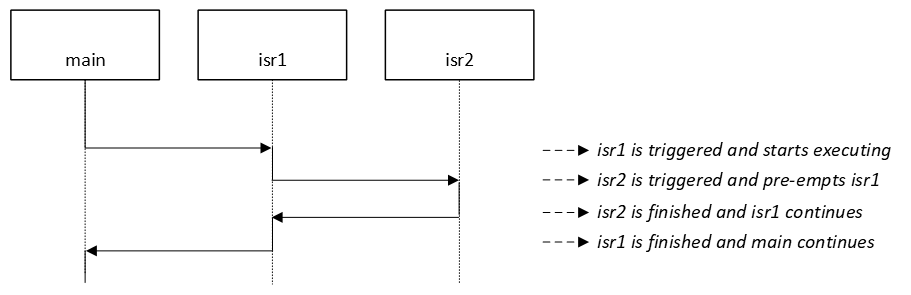

The N in NVIC stands for nested. Nested in the context of microcontrollers means that the handling of one interrupt service handler can be interrupted by another interrupt. For example:

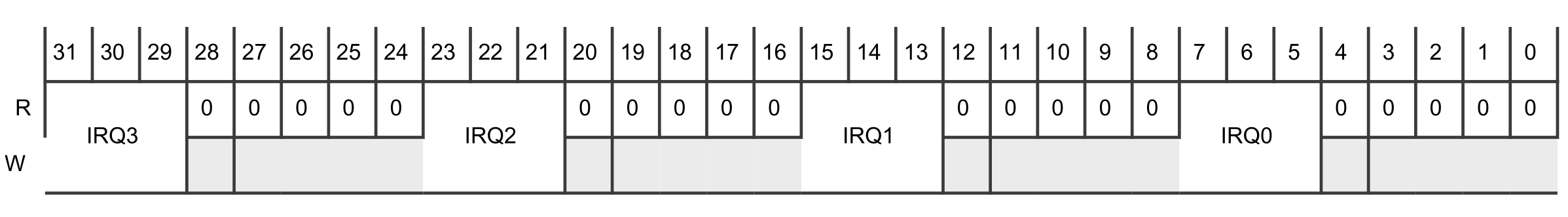

Interrupting another interrupt handler is only possible if the latter interrupt has higher priority. The reference manual section 3.3 describes that the MCXA153 supports 8 interrupt priority levels. These 8 levels are recorded in three bits. For the first four IRQ numbers, this is recorded in Interrupt Priority Register 0 (IPR0) as follows:

As can be seen in the image, each priority level is recorded in the MSB three bits of a byte. This results in the following priority levels in binary and decimal notation:

0b 000 00000 : 0 -> highest priority

0b 001 00000 : 32

0b 010 00000 : 64

0b 011 00000 : 96

0b 100 00000 : 128

0b 101 00000 : 160

0b 110 00000 : 192

0b 111 00000 : 224 -> lowest priority

Vector

The V in NVIC stands for vectored. Vectored in the context of microcontrollers means that the addresses of the interrupt handlers are stored in a table. In other words, this table stores function pointers (a.k.a. vectors) to the interrupt handlers. As soon as an interrupt is triggered, the microcontroller finds the corresponding address in this table and starts executing the interrupt handler.

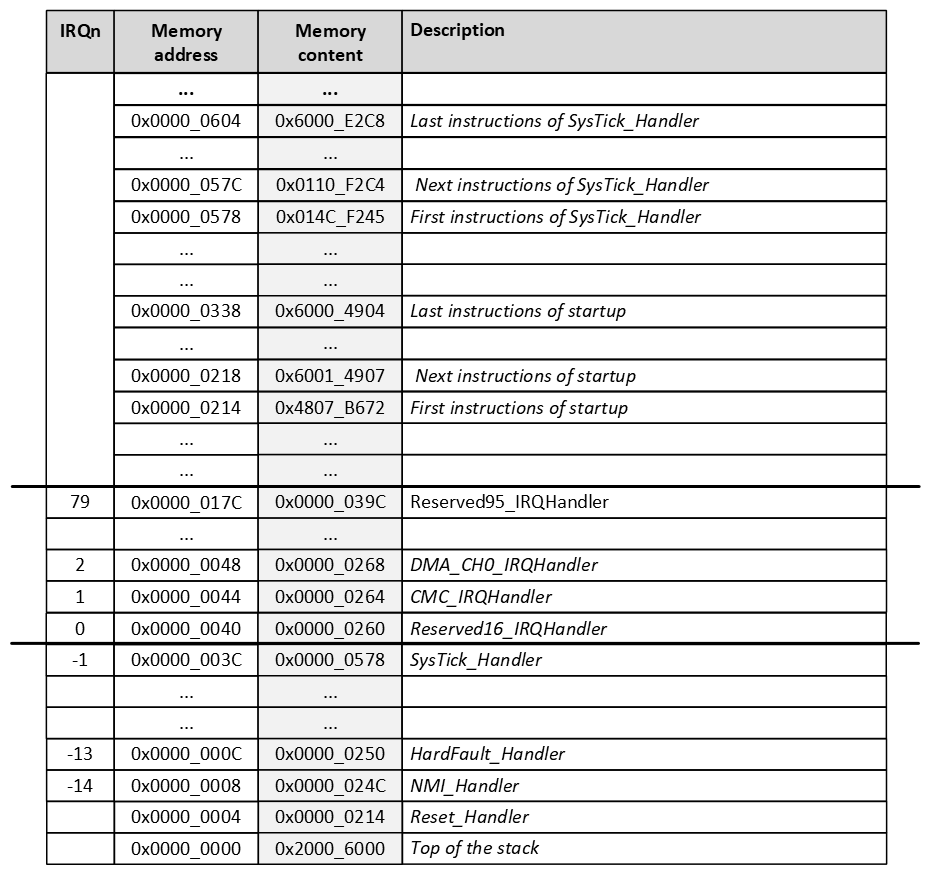

The index of an address in this table is also know as the interrupt number (IRQn). The implementation of the entire vector table for the MCXA153 is given in the reference manual in an appendix. An example of a (partial) vector table from one of the example projects is as follows:

The reference manual contains an appendix called NVIC_configuration.xlsx. In this document the IRQn (NVIC Interrupt ID) of all modules is given. For example, for the GPIO1 module: IRQn=72

The vector table is created by the linker and (normally) stored at the beginning of the flash memory. This is achieved in the examples in the startup file. This startup file uses placeholder names for all interrupt handlers. These are declared with the weak symbol, to denote that if the programmer doesn't provide an interrupt handler, the placeholder implementation should be used.

Special cases of interrupt priority

The NVIC will handle special priority cases as follows:

- New interrupt requested while an interrupt handler is executing?

- New priority higher than current priority?

- New interrupt handler pre-empts current interrupt handler

- New priority lower than or equal to current priority?

- New interrupt held in pending state

- Current handler continues and completes execution

- Previous priority level restored

- New interrupt handled if priority level allows

- New priority higher than current priority?

- Simultaneous interrupt requests and the same priority?

- Lowest interrupt IRQn is serviced first

CMSIS

The NVIC can be read and written by using its registers, similar to all other modules in the microcontroller. However, the NVIC is a module that is available in all Cortex-M microcontrollers. For that reason the CMSIS provides functions to access the NVIC.

Some functions that are often used are:

// Enable a device specific interrupt.

void NVIC_EnableIRQ(IRQn_Type IRQn);

// Set the priority for an interrupt.

void NVIC_SetPriority(IRQn_Type IRQn, uint32_t priority);

// Clear a device specific interrupt from pending.

void NVIC_ClearPendingIRQ(IRQn_Type IRQn);

// Globally enables interrupts.

void __enable_irq();

// Globally disables interrupts.

void __disable_irq();

Microcontroller vendors offer an enumerated type for the IRQn's. So instead of writing

void NVIC_EnableIRQ(31);

for enabling LPUART0 interrupts, the following can be used:

void NVIC_EnableIRQ(LPUART0_IRQn);

Setting the priority of an IRQn can be done in two ways:

- Directly by writing to the IPRn registers.

- By using the CMSIS function NVIC_SetPriority().

There is a difference, because the the CMSIS function assumes a priority value from 0 to 7. Whereas the IPRn registers should have a value as mentioned above. In other words, the following instructions have the same result:

NVIC_SetPriority(GPIO1_IRQn, 3);

NVIC->IPR[GPIO1_IRQn] = 96;

Invalid priority - extra

What happens if (by mistake) the following instruction is executed?

NVIC_SetPriority(GPIO1_IRQn, 96);

What happens next, depends on the implementation of the NVIC_SetPriority() function (see the file CMSIS/Core/Include/core_cm33.h included in all projects):

/**

\brief Set Interrupt Priority

\details Sets the priority of a device specific interrupt or a processor exception.

The interrupt number can be positive to specify a device specific interrupt,

or negative to specify a processor exception.

\param [in] IRQn Interrupt number.

\param [in] priority Priority to set.

\note The priority cannot be set for every processor exception.

*/

__STATIC_INLINE void __NVIC_SetPriority(IRQn_Type IRQn, uint32_t priority)

{

if ((int32_t)(IRQn) >= 0)

{

NVIC->IPR[((uint32_t)IRQn)]

= (uint8_t)((priority << (8U - __NVIC_PRIO_BITS)) & (uint32_t)0xFFUL);

}

else

{

SCB->SHPR[(((uint32_t)IRQn) & 0xFUL)-4UL]

= (uint8_t)((priority << (8U - __NVIC_PRIO_BITS)) & (uint32_t)0xFFUL);

}

}

For the MCXA153, __NVIC_PRIO_BITS is defined as 3. This means the provided priority will be bitwise left shifted 8 - 3 = 5 positions. With a value of 96 (=0b01100000), this means: (0b01100000 << 5) = 0b00000000.

The result is that the priority will be set to 0, which is the highest priority.

ISR considerations

When writing ISR's it is considered good practice to:

- Clear an interrupt in both the NVIC and module.

- Keep code as short as possible in the ISR.

- Declare global variables volatile that are used in the ISR to prevent the compiler from optimization.

GPIO input - interrupt

Resources: ese_driver_examples\gpio\input_interrupt

Goal

Know how to initialize and read a digital input pin by using interrupts in the GPIO module.

Initialization

It takes the following steps to configure P1_7 (SW3) for GPIO:

- Enable the PORT1 and GPIO1 modules in the MRCC module.

-

Initialize P1_7 for GPIO function in the PORT1 module.

No additional action is needed, because the default direction of P1_7 is input. These steps are exactly the same when compared to the polling example.

Using interrupts on a GPIO input pin requires two additional steps:

-

Enable the desired interrupt in the GPIO module.

- Enable GPIO1 interrupts in the NVIC module.

These steps are explained in more detail in the following sections.

1. Enable the PORT1 and GPIO1 modules

// Enable modules and leave others unchanged

// PORT1: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

// GPIO1: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC0_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC0_PORT1(1);

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC1_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC1_GPIO1(1);

// Release modules from reset and leave others unchanged

// PORT1: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

// GPIO1: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST0_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST0_PORT1(1);

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST1_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST1_GPIO1(1);

2. Initialize P1_7 for GPIO function

// Configure pin P1_7

// LK : [1] = Locks this PCR

// INV: [0] = Does not invert

// IBE: [1] = Digital Input Buffer Enable, otherwise pin is used for analog

// functions

// MUX: [0000] = Alternative 0 (GPIO)

// DSE: [0] = low drive strength is configured on the corresponding pin,

// if the pin is configured as a digital output

// ODE: [0] = Disables

// SRE: [0] = Fast

// PE: [0] = Disables

// PS: [0] = n.a.

PORT1->PCR[7] = PORT_PCR_LK(1) | PORT_PCR_IBE(1) | PORT_PCR_MUX(0);

3. Enable the desired interrupt in the GPIO module.

The GPIO module has an Interrupt Control Register (ICR) for each pin. These registers are organized in an array, so the ICR register for P1_7 is used as follows:

GPIO1->ICR[7]

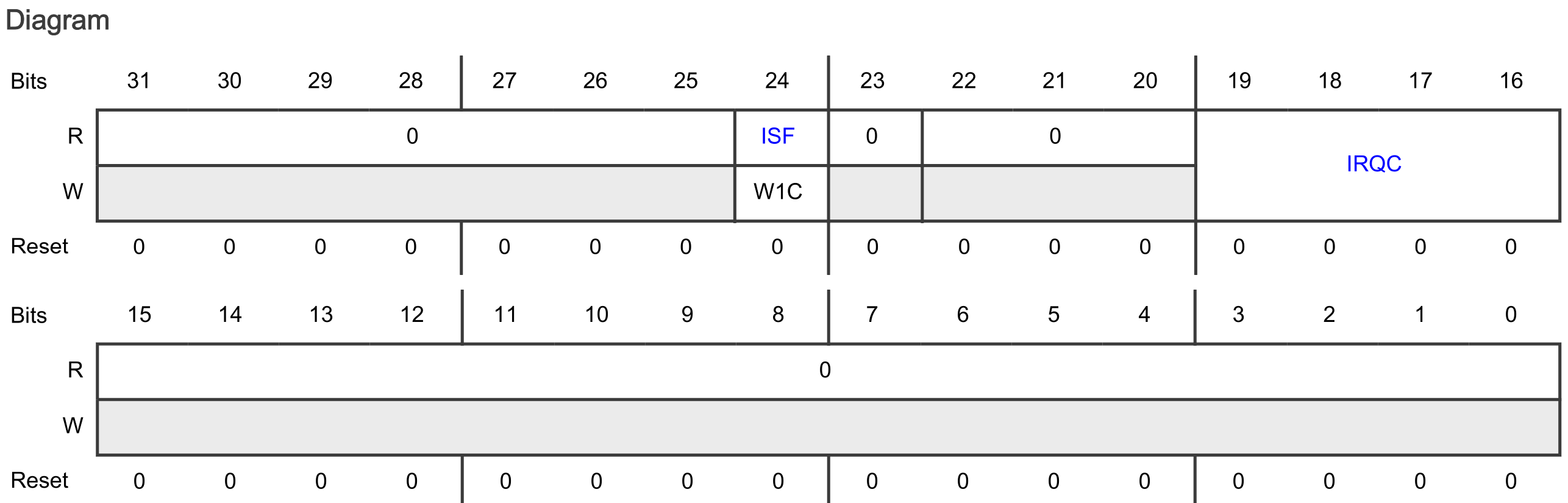

This register contains two bit fields as can be seen in the reference manual.

The bit fields are:

- ISF

- Means: Interrupt Status Flag

- Indicates whether the configured interrupt is detected. The pin interrupt configuration is valid in all digital pin muxing modes.

- The ISF bit field shows the text W1C. W1C means Write 1 to clear (w1c). See reference manual paragraph 1.5.4.

- The Interrupt Status Flag Register 0 (ISFR0) can also be used to check the interrupt status of P1_7. See reference manual paragraph 12.7.1.15

- IRQC

- The IRQC bit field contains 4 bits, giving a total of 16 ISF and DMA request configuration options.

- Out of reset, the IRQC bit field is 0b0000. Checking the IRQC configuration

- description in the reference manual: 0000b means that ISF is disabled.

Configuring P1_7 for setting the ISF and generating an interrupt on falling edges is done as follows:

// ISF: [1] = Clear the flag

// IRQC : [1010] = ISF and interrupt on falling edge

GPIO1->ICR[7] = GPIO_ICR_ISF(1) | GPIO_ICR_IRQC(0b1010);

4. Enable GPIO1 interrupts in the NVIC module.

Enabling interrupts for GPIO1 in the NVIC:

// Enable GPIO1 interrupts

NVIC_SetPriority(GPIO1_IRQn, 3);

NVIC_ClearPendingIRQ(GPIO1_IRQn);

NVIC_EnableIRQ(GPIO1_IRQn);

Interrupt handler

The interrupt handler for GPIO handles the interrupt request. The following must be done:

- Clear the interrupt in the NVIC.

- The same interrupt handler is executed for all GPIO1 pins. Check to make sure the interrupt was triggered by P1_7 (although strictly speaking, this is not necessary in this example as there is only one pin generating an interrupt).

- Clear the interrupt in the GPIO module.

- Handle the event.

The result is as follows:

void GPIO1_IRQHandler(void)

{

// Clear the interrupt

NVIC_ClearPendingIRQ(GPIO1_IRQn);

// Interrupt handler triggered by P1_7?

if((GPIO1->ISFR[0] & GPIO_ISFR_ISF7(1)) != 0)

{

// Clear the flag

GPIO1->ISFR[0] = GPIO_ISFR_ISF7(1);

// Handle the event

cnt++;

}

}

Note the use of a global variable called cnt. This variable is incremented on every interrupt generation. This is a global variable declared as follows:

static volatile uint32_t cnt = 0;

This variable is declared static, because the scope is limited to this file.

This variable is declared volatile, because the variable can change outside normal program flow (because it is used in an ISR). The compiler should not optimize any read/write operations.

Assignment

Change this example so it uses SW2 and the blue RGB LED.

Some tips:

- Find the pin that is connected to SW2 in the board schematic.

- Another GPIO module also requires another interrupt handler.

Assignment - Rotary encoder

Resources: ese_shieldv3_examples\encoder\gpio

Goal

To practice with the modules discussed so far.

Hardware requirements

- FRDM-MCXA153 board

- Rotary encoder, such as available on Shield V3 or Mikroe-1824 add-on board

- Type-C USB cable

Note. When using the Mikroe add-on board, different pins must be used!

Functional requirements

The application uses the RGB LED and a rotary encoder. It must implement the following functional requirements.

-

The application keeps track of the number of CW and CCW pulses.

a. pulses = 0: RGB LEDs off.

b. pulses > 0: Green LED on; Red LED off.

c. pulses < 0: Green LED off; Red LED on.

-

A CW pulse increments the number of pulses by 1.

- A CCW pulse decrements the number of pulses by 1.

- Pressing the encoder switch resets the pulses to 0.

- After a microcontroller reset, pulses is reset to 0.

Architecture

The Shield V3 shows an example of how to connect the hardware parts.

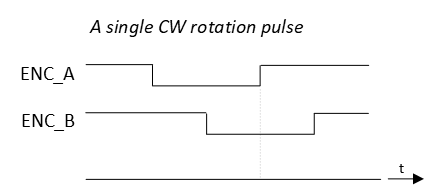

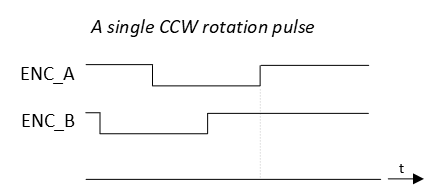

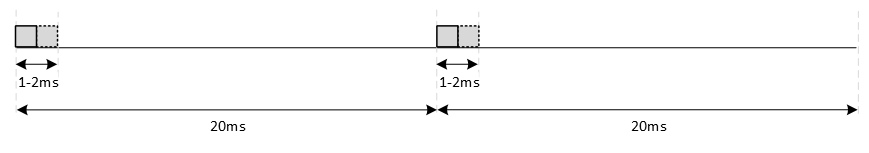

The ENC_A and ENC_B signals encode the rotation direction. An example timing diagram for a single clockwise (CW) rotation pulse:

And an example timing diagram for a single counter clockwise (CCW) rotation pulse:

Notice from both timing diagrams that on a rising edge of ENC_A, the sampled logic value of ENC_B is different for CW and for CCW rotations.

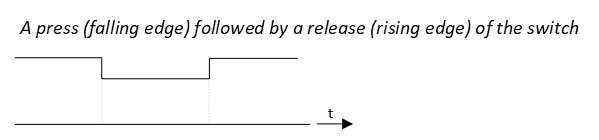

The ENC_SW signal reflects the logic state of the encoder switch as follows:

API

In order to create the functional requirements, the following API functions are prepared.

/*!

* \brief Initializes the RGB LED pins

*

* - Red LED | P3_12 | GPIO output

* - Green LED | P3_13 | GPIO output

* - Blue LED | P3_0 | GPIO output

*/

void gpio_output_init(void);

/*!

* \brief Initializes the encoder pins

*

* - ENC_A | P3_31 | GPIO input with interrupts enabled on rising edges

* - ENC_B | P2_7 | GPIO input

* - ENC_SW | P1_6 | GPIO input with interrupts enabled on both edges

*/

void encoder_init(void);

/*!

* \brief Resets the counted pulses.

*

* Resets the internal pulses counter to 0.

*/

void encoder_reset(void);

/*!

* \brief Returns the number of pulses in CW or CCW direction since last reset

*

* The function keeps track of the CW and CCW pulses. For every CW pulse, an

* internal counter is incremented. For every CCW pulse, that same counter is

* decremented.

*

* Meaning:

* - If the function returns 0, no pulses were counted or as much CW pulses as

* CCW pulses

* - If the function returns a value < 0, that much more number of CCW pulses

* were detected.

* - If the function returns a value > 0, that much more number of CW pulses

* were detected.

*

* \return The number of pulses counted since last reset

*/

int32_t encoder_pulses(void);

/*!

* \brief Detects if the switch was pressed.

*

* This firmware driver remembers if the switch was pressed with an internal

* flag. When this function is called, it resets the internal flag.

*

* \return True if the switch was pressed.

*/

bool encoder_sw_pressed(void);

/*!

* \brief Detects if the switch was released.

*

* This firmware driver remembers if the switch was released with an internal

* flag. When this function is called, it resets the internal flag.

*

* \return True if the switch was released.

*/

bool encoder_sw_released(void);

Implementation tips

- Start with the RGB LED GPIO output pins. Verify in main that the RGB works as expected.

For the encoder rotation detection:

- Configure ENC_A and ENC_B pins for GPIO input.

- Configure ENC_A pin to generate interrupts on rising edges.

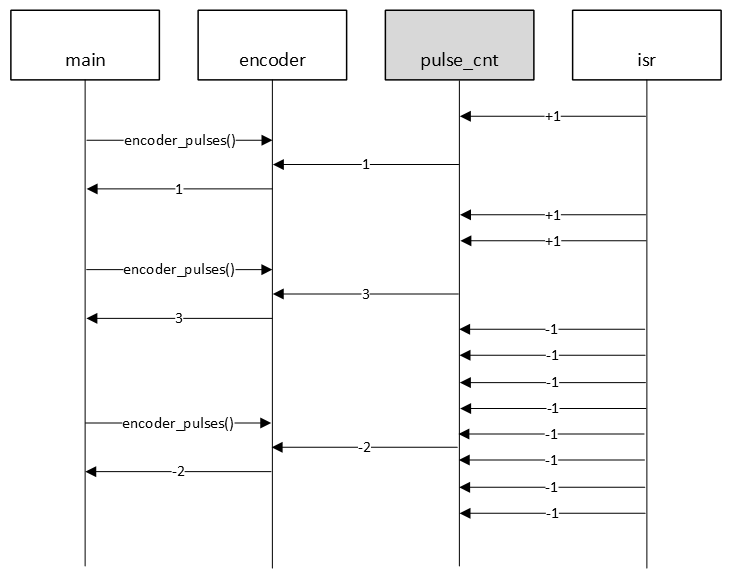

- When such an interrupt occurs, sample the logic input value of the ENC_B pin:

- if ENC_B pin = 0, then CW rotation, so internal counter pulse_cnt + 1

- if ENC_B pin = 1, then CCW rotation, so internal counter pulse_cnt - 1

This behaviour is illustrated in the following sequence diagram.

For the encoder switch:

- Configure ENC_SW for GPIO input.

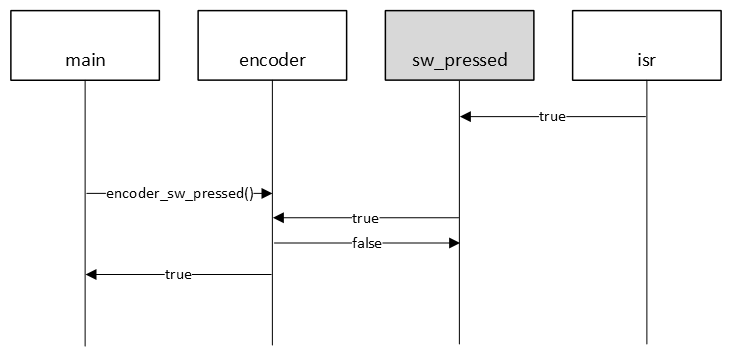

- Configure ENC_SW pin to generate interrupts on falling edges.

- When such an interrupt occurs, set an internal boolean flag sw_pressed indicating a SW press.

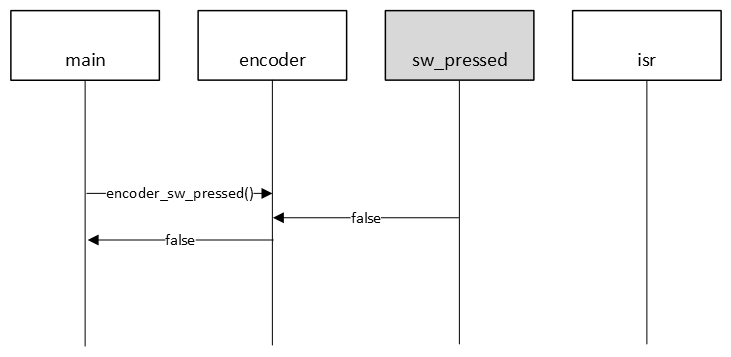

The following sequence diagram illustrates this behaviour for when the switch was pressed.

Or, the same example, but now when the switch was not pressed.

Timers - Introduction

Resources: none

Goal

To understand the general operation of timers/counters.

Timers/counter

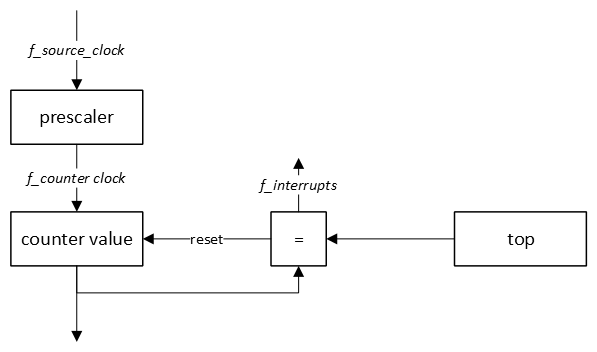

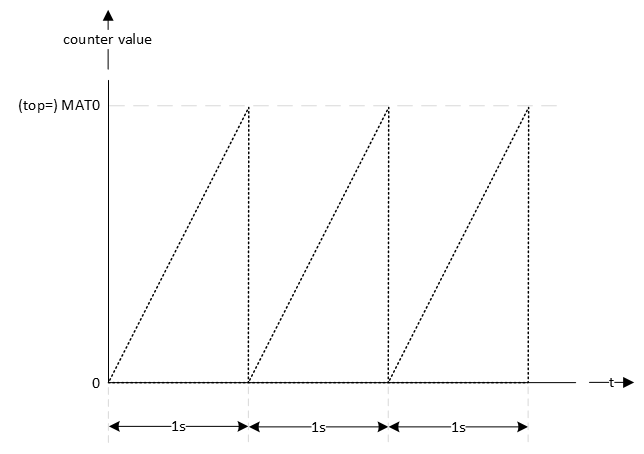

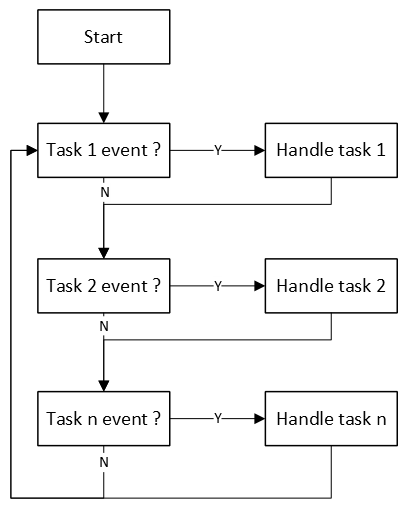

Generally speaking, timers are binary counters that count up/down in single steps to a top value and will start over again. This principle is depicted in the following block diagram.

The frequency at which interrupts are generated (f_interrupts) is equal to:

f_interrupts = f_source_clock / prescaler / (top + 1)

Or rewritten to the time between two interrupts (T_interrupts):

T_interrupts = T_source_clock * prescaler * (top + 1)

The number of pulses counted by most timers is equal to (top + 1), because the timer starts counting from 0. This, however, is implementation dependent.

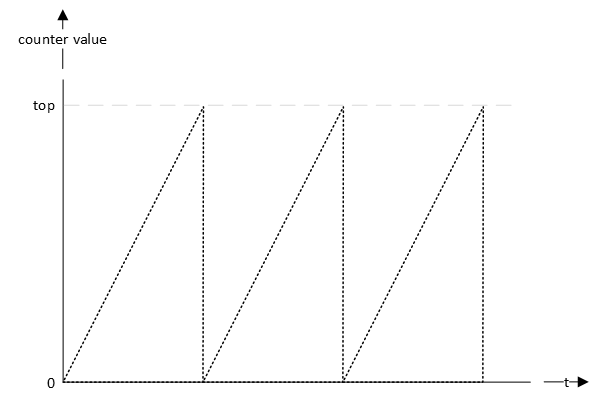

For a timer that counts up, the following general timing diagram is applicable.

Although this simplified basic representation is applicable for all timers, implementations of timer modules range from very basic to very complex. Timers can be used to capture and/or generate a variety of signals, such as square waves, PWM signals, pulse counting, etc.

SysTick

Resources: ese_driver_examples\systick\match_interrupt

Goal

To know what the SysTick module is and how to use the SysTick module for generating interrupts at a fixed interval.

System Tick Timer

The Cortex-M33 core comes with an integrated timer module, called the System Tick Timer (SysTick). This timer is often used by operating systems (OS), because this very same module is available in all Cortex-M microcontrollers. For applications that do not require an OS, the SysTick can be used for time keeping, time measurement, or as an interrupt source for tasks that need to be executed regularly.

Characteristics of the Cortex-M33 SysTick timer are:

- 24-bit down counter

- Clocked by the CPU_CLK

- The interrupt controller clock updates the SysTick counter. If this clock signal is stopped for low-power mode, the SysTick counter stops.

Accessing the SysTick module

The registers of the SysTick module are memory mapped. Clearing the CTRL register, for example, can be done as follows:

SysTick->CTRL = 0;

However, CMSIS provides a universal function to configure the SysTick module for all Cortex-M devices. The function prototype is:

uint32_t SysTick_Config(uint32_t ticks);

Verification of the default CPU clock setting

By default, the CPU is clocked with a frequency of 48 MHz. This means the SysTick timer is also clocked with 48 MHz. If we were to generate an interrupt every second, the CMSIS function would be called as follows:

// Generate an interrupt every 1s. Note that this will not work,

// because 480000000 > 2^24.

SysTick_Config(48000000);

However, 480000000 > 2^24, so this will not fit. The CMSIS function SysTick_Config() checks if the parameter ticks is within the 24-bit range. If not, the SysTick timer will not be started.

Instead of generating interrupts every second, let's generate an interrupt every millisecond. This is one thousand times faster than generating interrupts every second, so the function is called as follows:

// Generate an interrupt every 1ms

SysTick_Config(48000);

In general:

ticks = f_cpu / f_systick_interrupts

Interrupts are disabled by default and can be enabled by using the CMSIS compliant function:

// Enable interrupts

__enable_irq();

In this example, the while-loop is empty. With the Wait For Interrupt (WFI) instruction, the microcontroller can be put into a sleep mode.

while(1)

{

// Wait for interrupt

__WFI();

}

Finally, an interrupt handler is required. The CMSIS compliant function name is SysTick_Handler(). This name can also be found in the vector table in the startup file.

void SysTick_Handler(void)

{

// Toggle the green LED

GPIO3->PTOR = (1<<13);

}

Verification

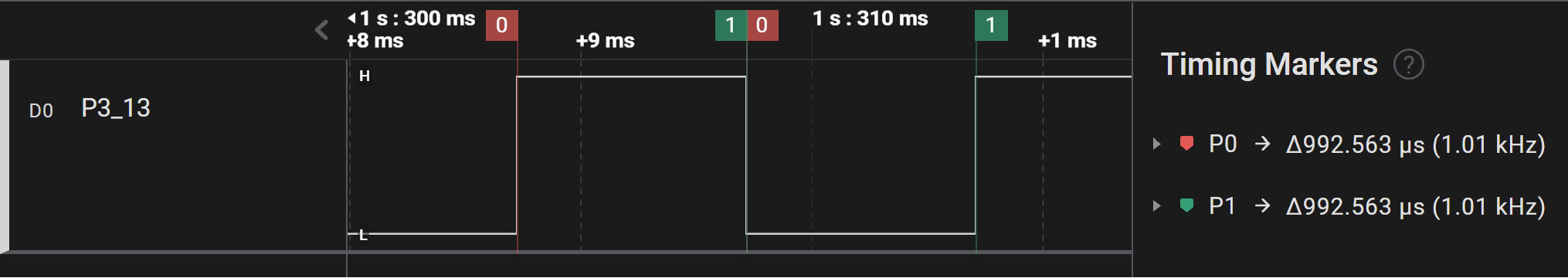

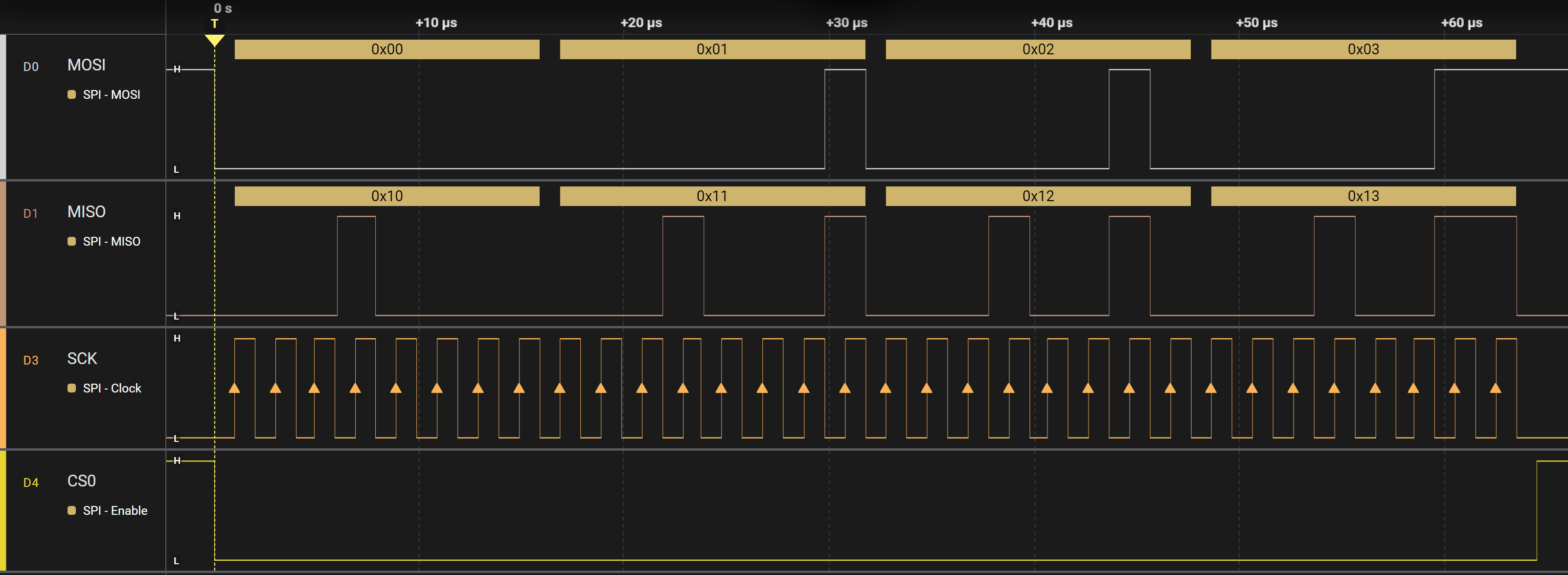

Verify that the green LED is on. The frequency is too high for the human eye to see the LED blinking. Connecting a logic analyzer to P3_13 shows:

This is very close to the expected 1 ms pulse width.

Assignment

- In main.c, add a global variable called ms as follows:

static volatile uint32_t ms = 0;

- Update the SysTick_Handler() as follows:

void SysTick_Handler(void)

{

ms++;

if((ms % 1000) == 0)

{

// Toggle the green LED

GPIO3->PTOR = (1<<13);

}

}

-

Build and run the application.

Q1Explain the result. -

ms is an 32-bit unsigned variable.

Q2How many days can be recorded if this variable is incremented every millisecond, before it starts from zero again? -

In Arduino, there is a millis() function that returns the number of milliseconds since microcontroller startup. Instead of using a function, we can use the ms variable. In main use the variable to create a blinky without delay. It toggles the red LED every 2 seconds (0.5Hz).

Critical sections

Resources: ese_general_examples\advanced\critical_section

Goal

To know how to protect a data object that requires multiple read or write operations.

Definitions

Before starting the discussion on how to protect a data object, it is good to be familiar with the following definitions:

Race condition

Anomalous behaviour due to unexpected critical dependence on the relative timing of events.

Critical section

A section of code which creates a possible race condition. The code section should only be executed by one process at a time.

Atomic

Indivisible access to any data object. For Cortex-M microcontrollers, the native object size is 32-bits. This means accessing data objects that are 32-bits or smaller takes a single clock cycle. This is indivisible. Data objects larger than 32-bits (such as structs), require more than one instruction to access (both reading and writing) and hence takes more then one clock cycle. This access could thus be interrupted.

Volatile

Directive for the compiler. Indicates that a variable may change outside of the control of some code. For example a module's register. Or a variable updated in an interrupt handler.

Introduction

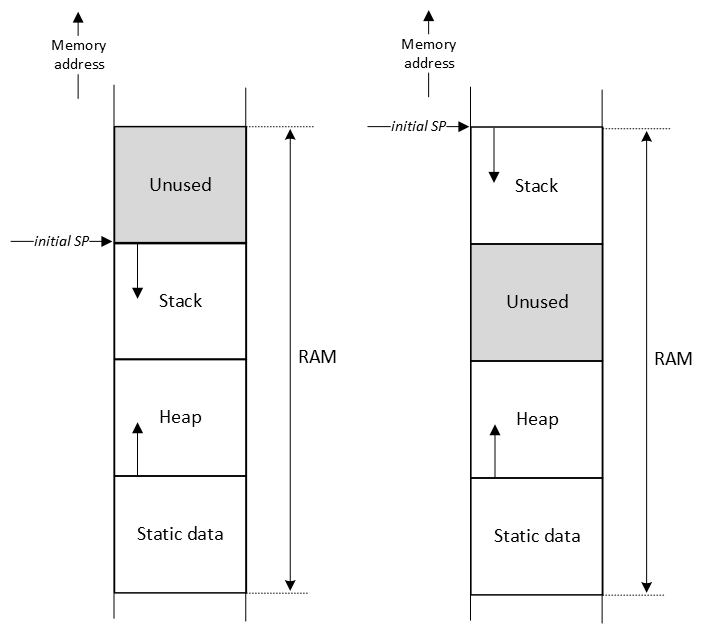

Accessing data in a microcontroller takes time. For example reading a 32-bit integer variable. Or writing a 16-bit value to a register. The time these actions take depend on the native object size of the microcontroller. For Cortex-M microcontrollers the native object size is 32-bits. Accessing objects of the native size or smaller are atomic.

It is common to work with data objects that are larger than the native object size. A struct is an example. Another example is all objects in an array. It takes more than one instruction to read or write the entire object. As multiple instructions can be interrupted, this might cause a race condition.

Example - no race condition

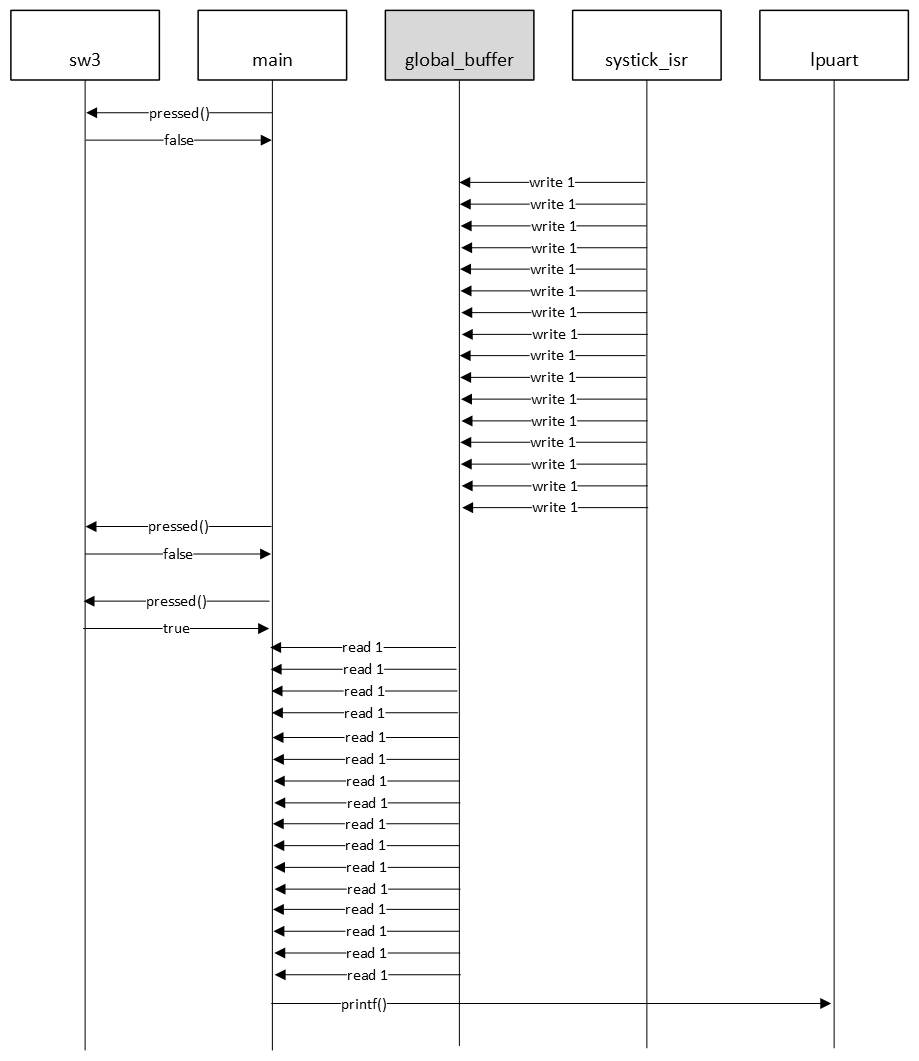

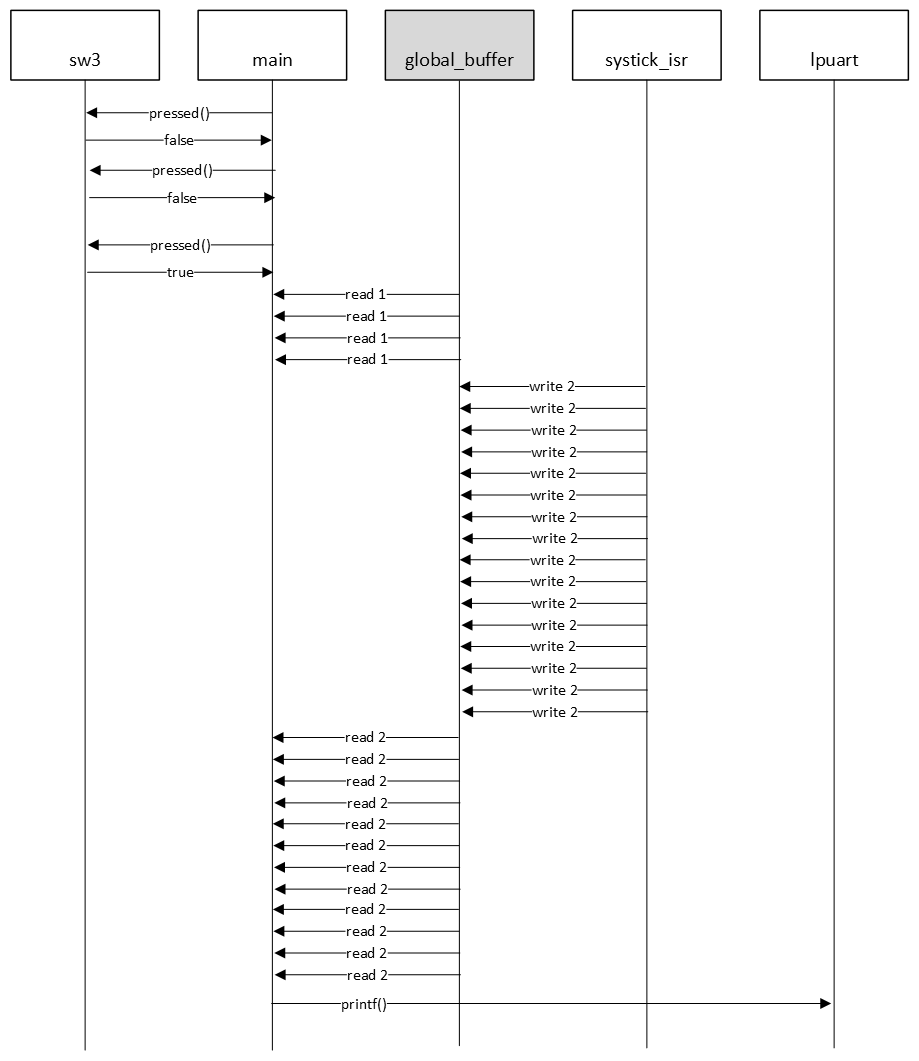

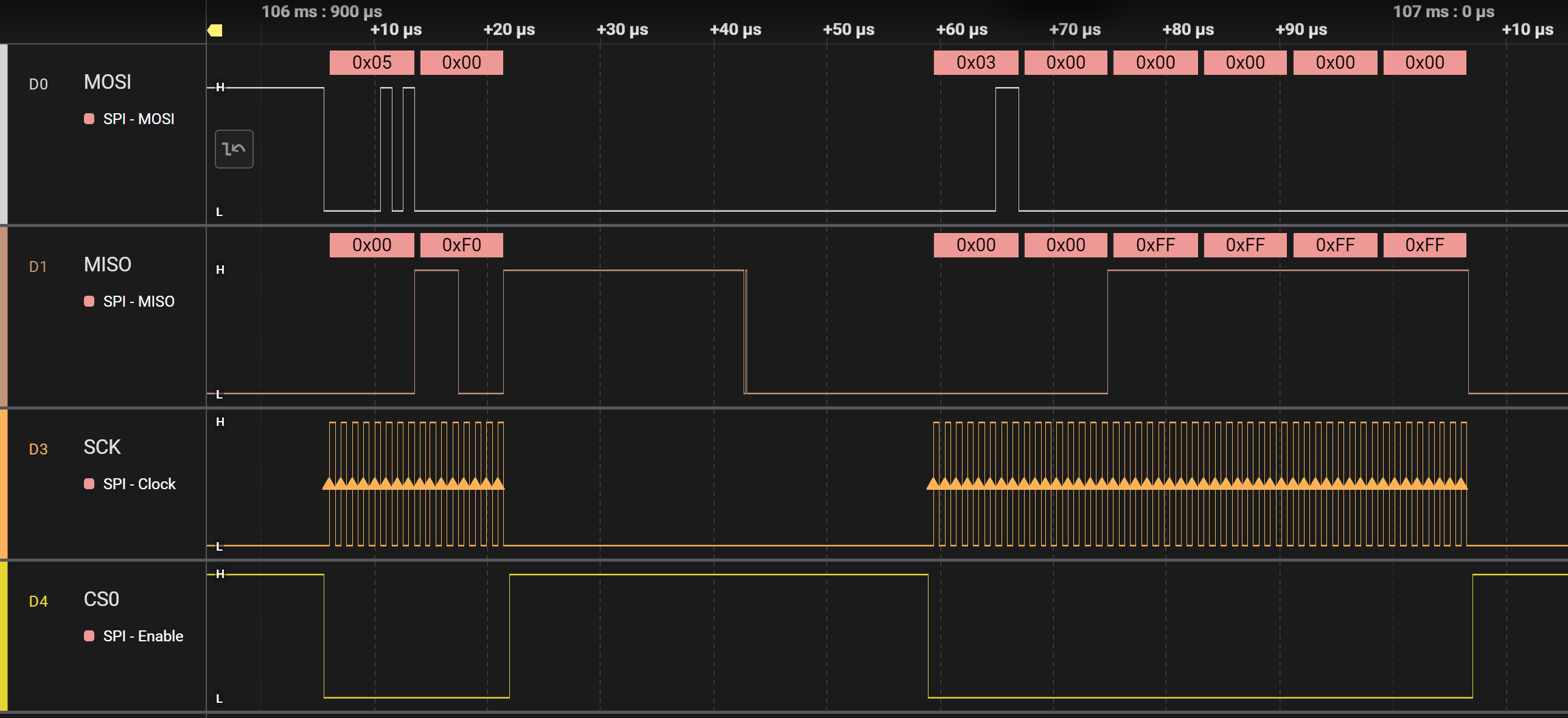

The following timing diagram shows the interaction between three processes: sw3, main and systick_isr. The main application checks if SW3 is pressed by using the sw3 process. If so, it will read all values from the shared data object global_buffer (in a for-loop) and print them using the LPUART. The systick_isr interrupt handler is executed every 1 second and writes the entire buffer with one and the same value, depending on the number of seconds passed.

This nice weather scenario produces, for example, the following output:

1111111111111111

3333333333333333

6666666666666666

9999999999999999

1111111111111111

2222222222222222

Example - Race condition

The execution of main depends on the input of the user. If SW3 is clicked within a certain time window, main might have started copying the global_buffer, but it gets interrupted by the systick_isr interrupt handler. This interrupt handler overwrites the entire shared object's content. As soon as the interrupt handler is finished the main continues copying with the updated value. This scenario is depicted in the following timing diagram.

This race condition scenario produces, for example, the following output:

1111111111111111

3333333333333333

6666666666666666

9999999999999999

1111222222222222 <-- Reading the global_buffer got unintentionally interrupted

2222222222222222

In this example, reading the global_buffer in main is the critical section. This section can be protected for pre-emption by globally disabling interrupts. This is done as follows with as few instructions as possible and makes sure that the previous state of the global interrupt setting is restored when the critical section is finished.

// Critical section start

uint32_t m = __get_PRIMASK();

__disable_irq();

// critical section goes here ...

__set_PRIMASK(m);

// Critical section end

The functions used in the code snippet above are part of the CMSIS. These functions are available for all Cortex-M microcontrollers.

Assignment

- Open the VCOM (115200-8n1) in a terminal application of your choice.

- Press SW3. Try to get the timing right and trigger the race condition (the buffer printing different values on a single SW3 click).

In the main-loop, there is an artificial delay. Increase the delay by a factor 10 as follows and try to trigger the race condition again.

// Artificial delay to increase the chance of interrupting this

// critical section

for(uint32_t d=0; d<200000; d++)

{}

Q1 Why does increasing the artificial delay make it easier to trigger the race condition?

Leave the increased delay in the code.

Q2 Protect the critical section from pre-emption by updating the code.

If implemented correctly you should observe two things:

- The printed line is always correct (showing one distinct character).

- Clicking SW3 twice quickly prints one or two characters, pauses for a little bit and then finishes printing.

Q3 Explain observation number 2.

Low-Power Timer

Resources: ese_driver_examples\lptmr\match_interrupt

Goal

To know what the LPTMR module is and how to use the LPTMR module for generating interrupts at a fixed interval.

LPTMR features

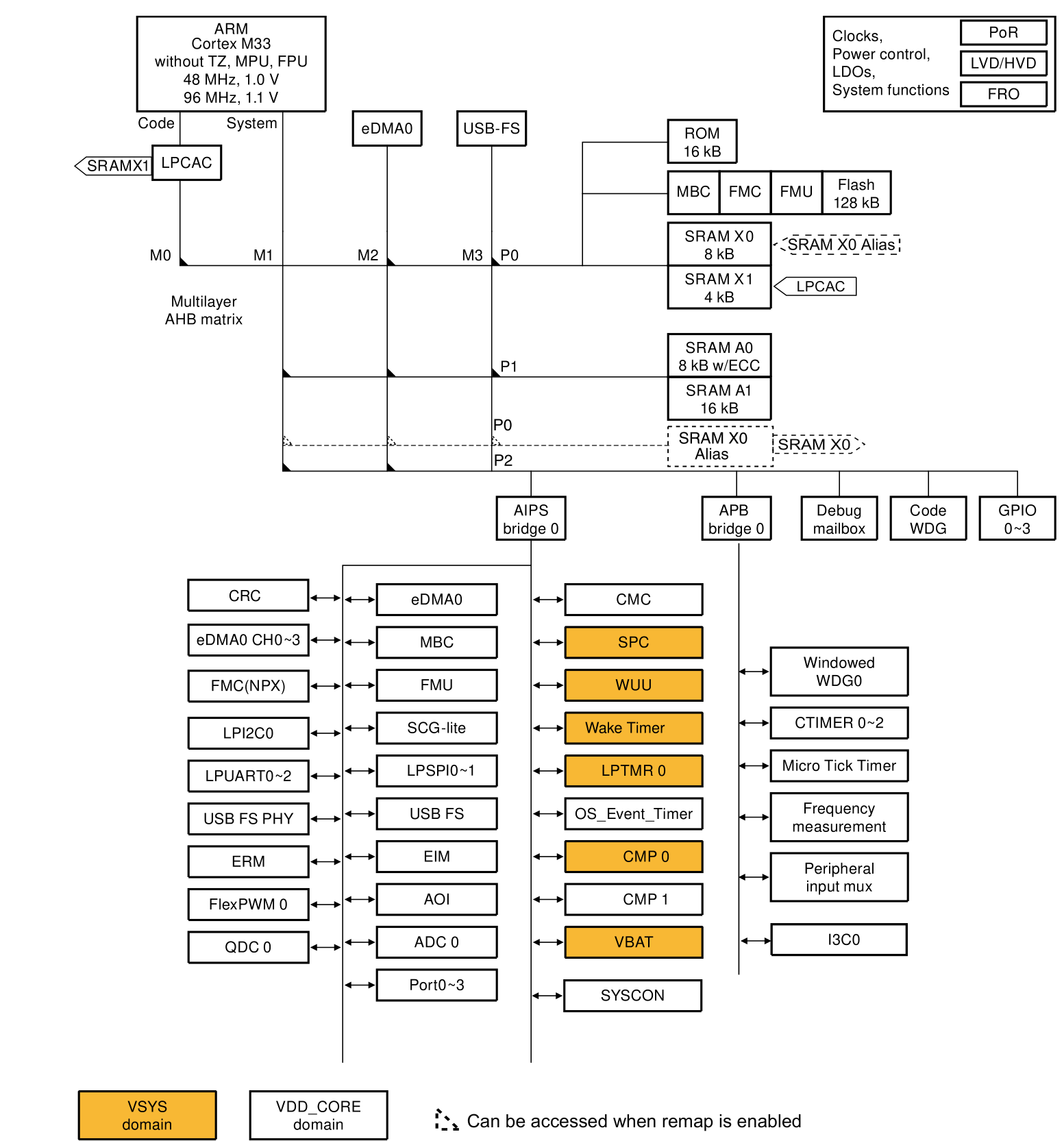

The MCXA153 has one instance of the LPTMR module. It is called LPTMR0. The LPTMR is described in the reference manual chapter 34.

Some characteristics of the LPTMR module are:

- 32-bit counter.

- Can be clocked from one of four sources determined by the PCS bit field in the LPTMR0->PSR register.

- The LPTMR allows the maximum clock frequency of 25 MHz.

- In low-power modes, LPTMR continues to operate normally.

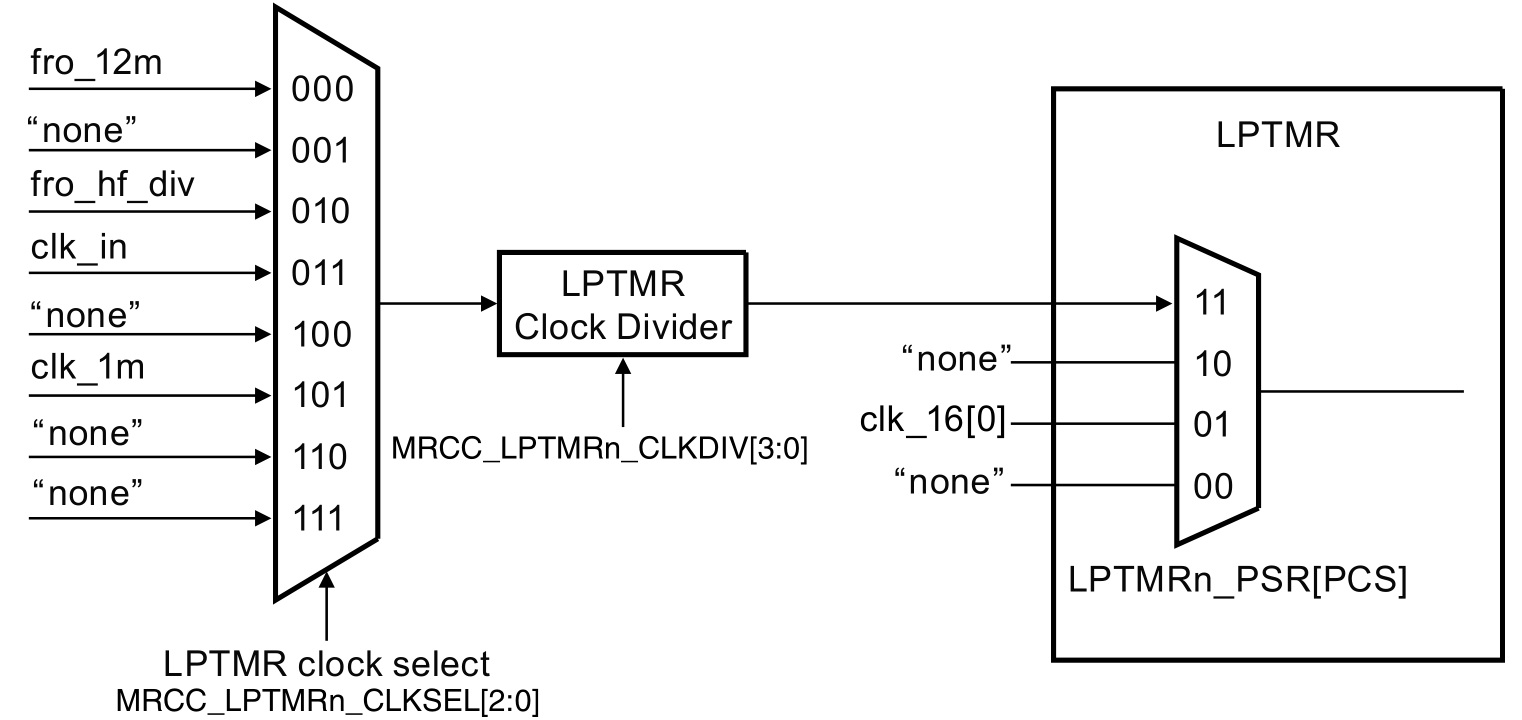

LPTMR clocking

Clocking the LPTMR is established by configuring several bits in registers of the MRCC- and LPTMR module. This is depicted in the following image.

An example

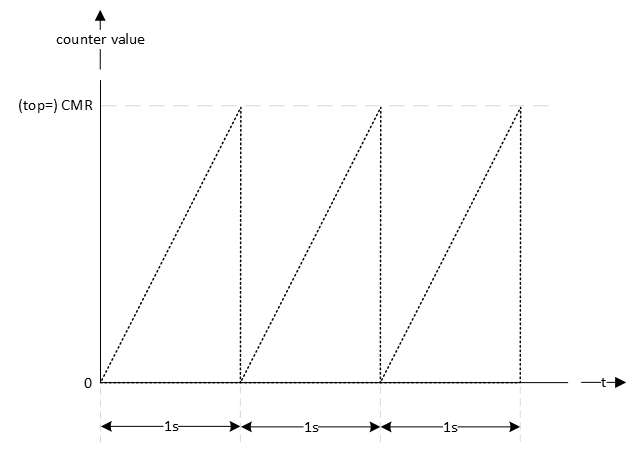

In this example, the LPTMR is configured to generate an interrupt every second. This is depicted in the following timing diagram. CMR is the compare register and when the counter value matches the CMR register, the counter should reset.

First the clock source for the timer should be established. This is application dependent, but let's choose the CLK_1M. Dividing this clock by 1 million generates an interrupt every second. The reference manual chapter 34.5 describes how to initialize LPTMR0.

void lptmr0_init(void)

{

// Set clock source

// MUX: [101] = CLK_1M

MRCC0->MRCC_LPTMR0_CLKSEL = MRCC_MRCC_LPTMR0_CLKSEL_MUX(0b101);

// Set clock divider

// HALT: [0] = Divider clock is running

// RESET: [0] = Divider isn't reset

// DIV: [0000] = divider value = (DIV+1) = 1

MRCC0->MRCC_LPTMR0_CLKDIV = 0;

// From section 34.5 Initialization (NXP, 2024)

//

// Perform the following procedure to initialize LPTMR:

// 1. Configure Control Status (CSR) for the selected mode and pin

// configuration, when CSR[TEN] is 0. This resets the counter and clears

// the flag.

// 2. Configure Prescaler and Glitch Filter (PSR) with the selected clock

// source and prescaler or glitch filter configuration.

// 3. Configure Compare (CMR) with the selected compare point.

// 4. Write 1 to CSR[TEN] to enable LPTMR.

// 1.

//

// - TDRE : [0] = Timer DMA request disable

// - TCF : [1] = Clears the Timer Compare Flag

// - TIE : [0] = Timer interrupt disable

// - TPS : [00] = Timer Pin Select is not used, leave at default value

// - TPP : [0] = Timer Pin Polarity is not used, leave at default value

// - TFC : [0] = CNR is reset whenever TCF is set

// - TMS : [0] = Time Counter mode

// - TEN : [0] = LPTMR is disabled

LPTMR0->CSR = LPTMR_CSR_TCF(1);

// 2.

//

// - PRESCALE : [0000] = n.a.

// - PBYP : [1] = Prescaler and glitch filter disable

// - PCS : [11] = Clock 3 is Combination of clocks configured in

// MRCC_LPTMR0_CLKSEL[MUX] field in SYSCON module. The Clock

// frequency must be less than 25 MHz to be used as a clock

// for the Low Power Timers.

LPTMR0->PSR = LPTMR_PSR_PBYP(1) | LPTMR_PSR_PCS(0b11);

// 3.

//

// Generate an interrupt every second

LPTMR0->CMR = 1000000-1;

// 4.

//

// - TDRE : [0] = Timer DMA request disable

// - TCF : [1] = Clears the Timer Compare Flag

// - TIE : [1] = Timer interrupt enable

// - TPS : [00] = Timer Pin Select is not used, leave at default value

// - TPP : [0] = Timer Pin Polarity is not used, leave at default value

// - TFC : [0] = CNR is reset whenever TCF is set

// - TMS : [0] = Time Counter mode

// - TEN : [1] = LPTMR is enable

LPTMR0->CSR = LPTMR_CSR_TCF(1) | LPTMR_CSR_TIE(1) | LPTMR_CSR_TEN(1);

// Enable Interrupts

NVIC_SetPriority(LPTMR0_IRQn, 0);

NVIC_ClearPendingIRQ(LPTMR0_IRQn);

NVIC_EnableIRQ(LPTMR0_IRQn);

}

The interrupt handler is implemented as follows. The name of the handler is defined in the startup file.

void LPTMR0_IRQHandler(void)

{

// Clear pending IRQ

NVIC_ClearPendingIRQ(LPTMR0_IRQn);

// Clear status flag by writing 1

LPTMR0->CSR |= LPTMR_CSR_TCF_MASK;

// Handle the event

lptmr0_timeout_flag = true;

}

Notice the use of the global variable lptmr0_timeout_flag. This flag can be checked in the main application. The following example checks if the flag is true, set it to false en toggle the green LED.

while(1)

{

// LPTMR flag true?

if(lptmr0_timeout_flag == true)

{

// Set it false

lptmr0_timeout_flag = false;

// Toggle green LED

GPIO3->PTOR = (1<<13);

}

}

Assignment

There is more than one way to slow down the generation of interrupts. For example, for generating interrupts with an interval twice as long:

- Set the functional divider to 2, by setting the DIV bit field to 1 in the MRCC0->MRCC_LPTMR0_CLKDIV register.

- Enable and set the prescaler to 2 in the LPTMR0->PSR register.

- Double the value written in the LPTMR0->CMR register.

Implement all of the above. If correct, the green LED toggles approximately every 8 seconds.

Note

Although not used in this example project, reading the LPTMR counter value is different compared to the other timers. This is what is mentioned in the reference manual in section 34.3.5:

You cannot initialize CNR but can read it at any time. On each read of CNR, you must first write a value to it. This synchronizes and registers the current value of CNR into a temporary register. The contents of the temporary register are returned on each read of CNR.

So, reading the counter value is done as follows:

// Reading the CNR value requires that it is written first (see reference manual

// section 34.3.5)

LPTMR0->CNR = 0;

uint32_t cnr_value = LPTMR0->CNR;

Standard Counter or Timer - match

Resources: ese_driver_examples\ctimer\match_interrupt

Goal

Know how to use the standard counter or timer (CTIMER) module to periodically generate interrupts.

Standard Counter or Timer

The MCXA153 microcontroller features three Standard Counter or Timer (CTIMER) modules. Features of each module include:

- 32-bit binary counter

- 32-bit prescaler

- Four 32-bit capture registers to take a snapshot of the binary counter when an input signal transitions

- Four 32-bit match registers

- To control timer operations

- Generate external outputs

- Setup for PWM operation, allowing up to three single-edged controlled PWM outputs

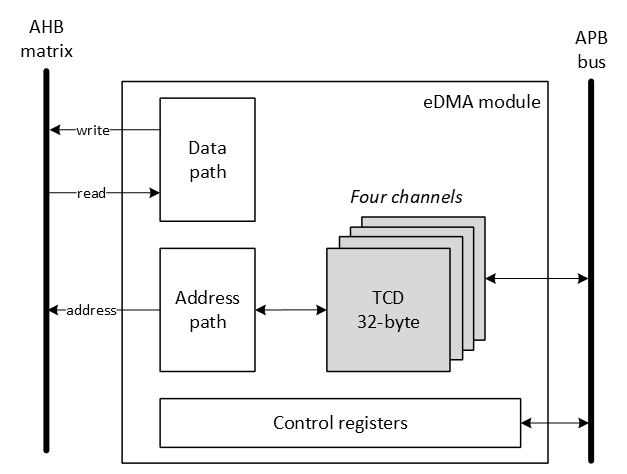

CTIMER clocking

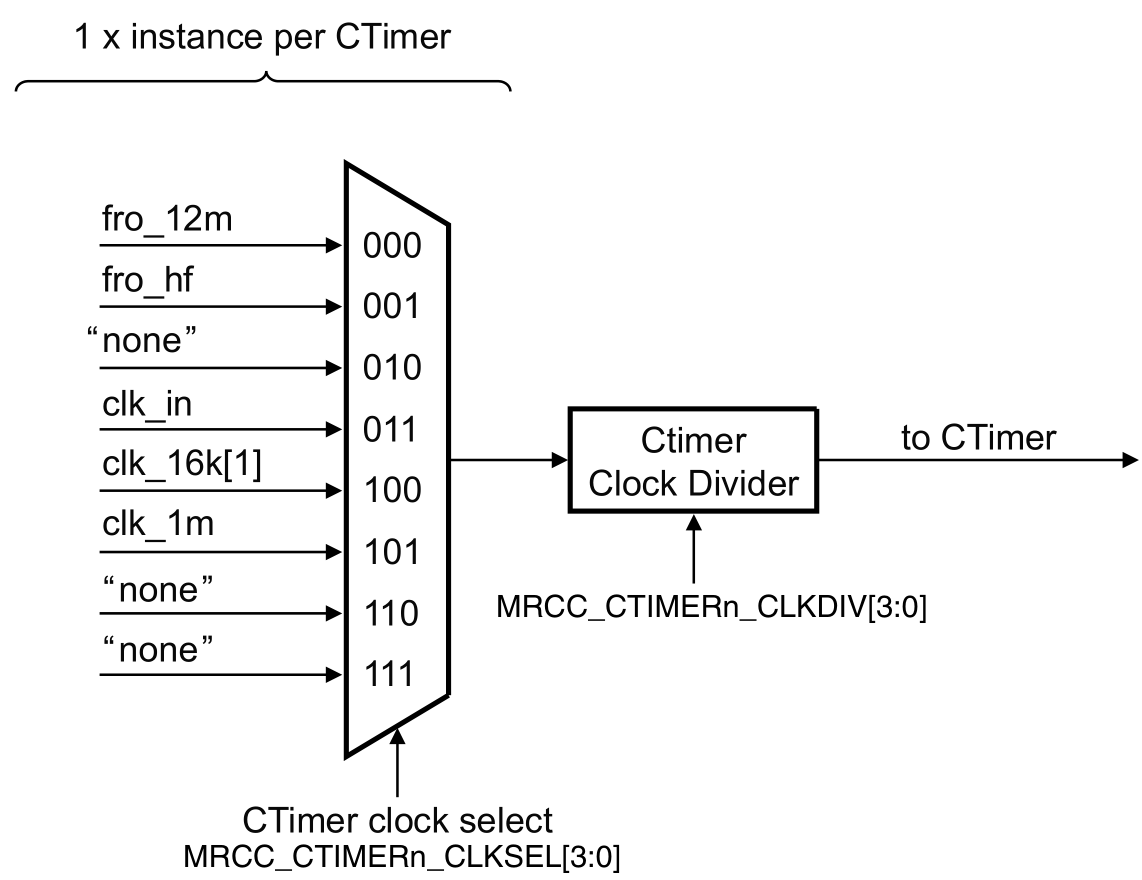

Clocking the CTIMER is depicted in the following image.

CTIMER in match interrupt mode

In this example, CTIMER 1 channel 0 is configured to generate an interrupt every second. This is depicted in the following timing diagram. MAT0 is the compare register and when the counter value matches the MAT0 register, the counter must be reset.

Generating interrupts at a regular interval with a CTIMER can be done by following the initialization steps as described in the reference manual paragraph 26.1.5.

- Select a clock source for the CTIMER using MRCC_CTIMER0_CLKSEL, MRCC_CTIMER1_CLKSEL, and MRCC_CTIMER2_CLKSEL registers.

- Enable the clock to the CTIMER via the CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN[CTIMER0_CLK_EN], CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN[CTIMER1_CLK_EN], and CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN[CTIMER2_CLK_EN] fields. This enables the register interface and the peripheral function clock.

- Clear the CTIMER peripheral reset using the MRCC_GLB_RST0 registers.

- Each CTIMER provides interrupts to the NVIC. See MCR and CCR registers in the CTIMER register section for match and capture events. For interrupt connections, see the attached NVIC spreadsheet.

- Select timer pins and pin modes as needed through the relevant PORT registers.

- The CTIMER DMA request lines are connected to the DMA trigger inputs via the DMAC0_ITRIG_INMUX registers (See Memory map and register definition). Note that timer DMA request outputs are connected to DMA trigger inputs.

As an example, CTIMER1 will be configured to generate interrupts with a frequency of 1 Hz. This doesn't require the use of pins or DMA requests, so steps 5. and 6. can be omitted. The other steps are explained in more detail in the following sections.

1. Select a clock source

The source clock is selected in the MRCC module. From the available options, 1 MHz is selected. Furthermore, the source clock is configured to run and the divider is set to 1. This divider can be seen as an additional prescaler (available in the MRCC module).

// MUX: [101] = CLK_1M

MRCC0->MRCC_CTIMER1_CLKSEL = MRCC_MRCC_CTIMER1_CLKSEL_MUX(0b101);

// HALT: [0] = Divider clock is running

// RESET: [0] = Divider isn't reset

// DIV: [0000] = divider value = (DIV+1) = 1

MRCC0->MRCC_CTIMER1_CLKDIV = 0;

2. Enable the clock to the CTIMER

The CTIMER module interface and function clock are disabled by default. These are enabled in the SYSCON module as follows:

// CTIMER1_CLK_EN: [1] = CTIMER 1 function clock enabled

SYSCON->CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN |= SYSCON_CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN_CTIMER1_CLK_EN(1);

3. Clear the CTIMER peripheral reset

Similar to all other modules, the CTIMER needs to be enabled and released from reset in the MRCC module:

// Enable modules and leave others unchanged

// CTIMER1: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC0_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC0_CTIMER1(1);

// Release modules from reset and leave others unchanged

// CTIMER1: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST0_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST0_CTIMER1(1);

4. Setup NVIC

In order to generate interrupts at the desired interval of 1 Hz, the prescaler and top value must be configured.

Using the equation from timers introduction:

f_interrupts = f_source_clock / prescaler / (top + 1)

1Hz = 1 MHz / prescaler / (top + 1)

This yields a single equation with two unknowns. However, a value can be chosen for one of the unknowns:

1Hz = 1MHz / 1000 / (top + 1)

1Hz = 1 kHz / (top + 1)

=>

(top + 1)= 1 kHz / 1 Hz

(top + 1)= 1000

Finally, check if both the chosen and calculated value fit within 32-bit registers. This is true, because in both cases 1000 < 2^32.

Each timer has four match channels. For generating a single interrupt, the selected channel doesn't matter, so let's select match register channel 0 (MR0). Three bits need to be configured for MR0:

- MR0S - Stop on MR0 Stops Timer Counter (TC) and Prescale Counter (PC), and turns TCR[CEN] to 0 if MR0 matches Timer Counter (TC). Must be 0, because the timer must keep on running to generate interrupt periodically

- MR0R - Reset on MR0 Resets Timer Counter (TC) if MR0 matches its value. Must be 1, because the timer must restart from zero on a match.

- MR0I - Interrupt on MR0 Generates an interrupt when MR0 matches the value in Timer Counter (TC). Must be 1, because an interrupt must be generated.

// Specifies the prescale value. 1 MHz / 1000 = 1 kHz

CTIMER1->PR = 1000-1;

// Match value for match register 0. 1 kHz / 1000 = 1 Hz

CTIMER1->MR[0] = 1000-1;

// MR0S: [0] = Does not stop Timer Counter (TC) if MR0 matches Timer Counter

// (TC)

// MR0R: [1] = Resets Timer Counter (TC) if MR0 matches its value.

// MR0I: [1] = Generates an interrupt when MR0 matches the value in Timer

// Counter (TC).

CTIMER1->MCR |= CTIMER_MCR_MR0R(1) | CTIMER_MCR_MR0I(1);

Finally, interrupts are enabled in the NVIC and the CTIMER is enabled.

// Enable Interrupts

NVIC_SetPriority(CTIMER1_IRQn, 7);

NVIC_ClearPendingIRQ(CTIMER1_IRQn);

NVIC_EnableIRQ(CTIMER1_IRQn);

// CEN: [1] = Enables the counters.

CTIMER1->TCR |= CTIMER_TCR_CEN(1);

Interrupt handler

The following interrupt handler clears the flag in the NVIC and CTIMER1 and sets a global flag that can be polled in the main application.

void CTIMER1_IRQHandler(void)

{

// Clear pending IRQ

NVIC_ClearPendingIRQ(CTIMER1_IRQn);

// Interrupt generated by MR0?

if((CTIMER1->IR & CTIMER_IR_MR0INT(1)) != 0)

{

// Clear status flag by writing 1

CTIMER1->IR |= CTIMER_IR_MR0INT(1);

// Handle the event

ctimer1_0_timeout_flag = true;

}

}

In main, this flag is polled and used to toggle the green LED as follows:

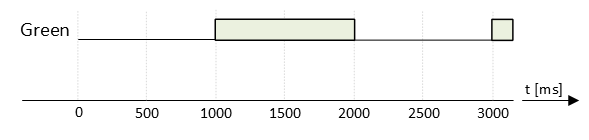

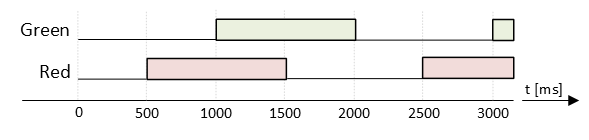

Assignment

Use CTIMER1 match register 1 (MR1) to additionally generate the following signal for the red LED:

Tips:

- Both signals have the same frequency, so they can share a CTIMER.

- Only one of both channels should be configured to reset the timer when a match occurs.

- Add another shared variable to let main know an interrupt occurred:

extern volatile bool ctimer1_1_timeout_flag;

Standard Counter or Timer - PWM

Resources: ese_driver_examples\ctimer\pwm

Goal

Know how to use the standard counter or timer (CTIMER) module to generate a PWM signal.

CTIMER in PWM mode

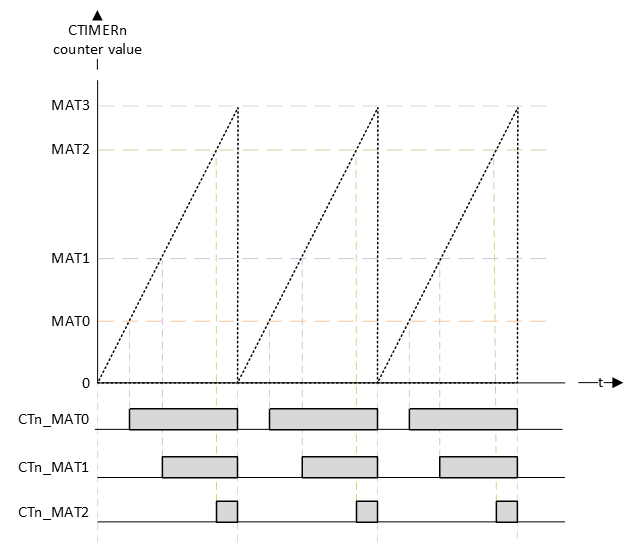

The four 32-bit match registers in a CTIMER can be configured for PWM operation, allowing up to three single-edged controlled PWM outputs. The following timing diagram shows the interactions between the CTIMER value, the match registers and the output signal.

The timing diagram shows that the top value is the MAT3 register. The other MAT registers can be used for compare matches. If a match occurs, the corresponding pin will generate a rising edge. At the beginning of the PWM cycle, all channel pins will generate a falling edge (unless their match value is zero).

CTIMER configuration

The configuration of the CTIMER is done by following the initialization steps as described in the reference manual paragraph 26.1.5.

- Select a clock source for the CTIMER using MRCC_CTIMER0_CLKSEL, MRCC_CTIMER1_CLKSEL, and MRCC_CTIMER2_CLKSEL registers.

- Enable the clock to the CTIMER via the CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN[CTIMER0_CLK_EN], CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN[CTIMER1_CLK_EN], and CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN[CTIMER2_CLK_EN] fields. This enables the register interface and the peripheral function clock.

- Clear the CTIMER peripheral reset using the MRCC_GLB_RST0 registers.

- Each CTIMER provides interrupts to the NVIC. See MCR and CCR registers in the CTIMER register section for match and capture events. For interrupt connections, see the attached NVIC spreadsheet.

- Select timer pins and pin modes as needed through the relevant PORT registers.

- The CTIMER DMA request lines are connected to the DMA trigger inputs via the DMAC0_ITRIG_INMUX registers (See Memory map and register definition). Note that timer DMA request outputs are connected to DMA trigger inputs.

As an example, a CTIMER1 will be used to create a PWM signal for dimming the red RGB LED to 10%. The PWM signal of will get a frequency of 1kHz. This doesn't require the use of interrupts or DMA requests, so steps 4. and 6. can be omitted. The other steps are explained in more detail in the following sections.

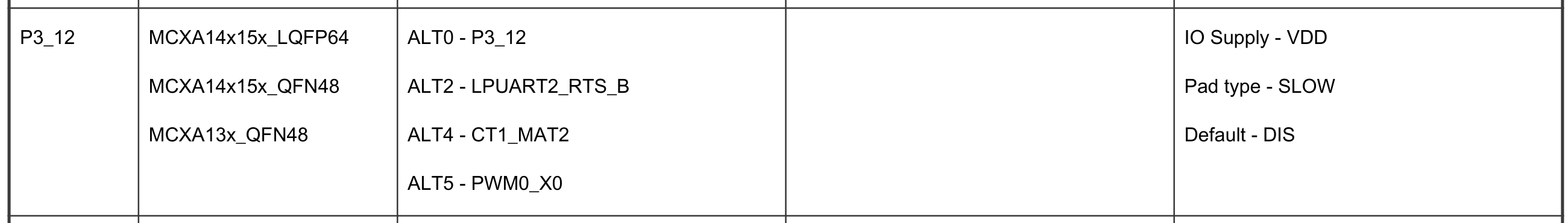

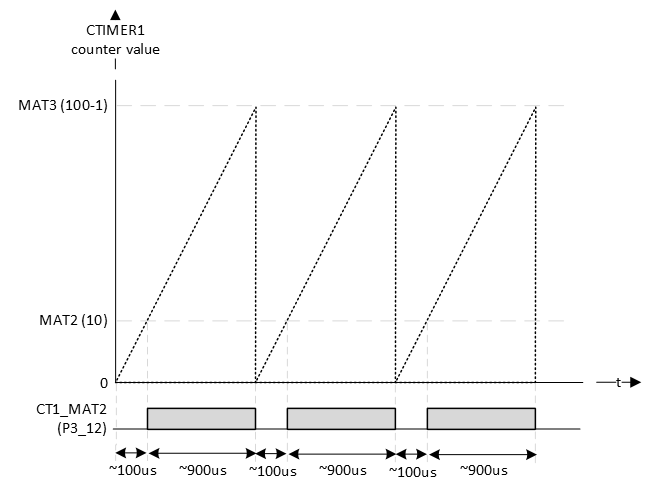

The red RGB LED is connected to P3_12. The reference manual shows that this pin is connected to CTIMER1 match register channel 2 (CT1_MAT2). This is mux alternative 4 (ALT4).

1. Select a clock source

The source clock is selected in the MRCC module. From the available options, 1MHz is selected. Furthermore, the source clock is configured to run and the divider is set to 1. This divider can be seen as an additional prescaler (available in the MRCC module).

// MUX: [101] = CLK_1M

MRCC0->MRCC_CTIMER1_CLKSEL = MRCC_MRCC_CTIMER1_CLKSEL_MUX(0b101);

// HALT: [0] = Divider clock is running

// RESET: [0] = Divider isn't reset

// DIV: [0000] = divider value = (DIV+1) = 1

MRCC0->MRCC_CTIMER1_CLKDIV = 0;

2. Enable the clock to the CTIMER

The CTIMER module interface and function clock are disabled by default. These are enabled in the SYSCON module as follows:

// CTIMER1_CLK_EN: [1] = CTIMER 1 function clock enabled

SYSCON->CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN |= SYSCON_CTIMERGLOBALSTARTEN_CTIMER1_CLK_EN(1);

3. Clear the CTIMER peripheral reset

Similar to all other modules, the CTIMER needs to be enabled and released from reset in the MRCC module:

// Enable modules and leave others unchanged

// CTIMER1: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC0_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC0_CTIMER1(1);

// Release modules from reset and leave others unchanged

// CTIMER1: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST0_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST0_CTIMER1(1);

5. Select timer pins and pin modes

By setting a prescaler of 10, the f_counter = 1 MHz / 10 = 100 kHz.

If the top (MAT3) value is set to (100-1), then f_pwm = 100 kHz / 100 = 1 kHz.

It also means that valid match register values are 0 to 100. So the precision of the PWM duty cycle is 100 steps.

Setting a duty cycle of 10% is done by writing 10 to the MAT2 register.

// Specifies the prescale value. 1 MHz / 10 = 100 kHz

CTIMER1->PR = 10-1;

// Match value: 100 kHz / 100 = 1 kHz

//

// In PWM mode, use match channel 3 to set the PWM cycle length. The other

// channels can be used for matches

CTIMER1->MR[2] = 10;

CTIMER1->MR[3] = 100-1;

Furthermore, the the three bits for each channel must be configured:

// MR2S: [0] = Does not stop Timer Counter (TC) if MR0 matches Timer Counter

// (TC)

// MR2R: [0] = Resets Timer Counter (TC) if MR0 matches its value.

// MR2I: [0] = No interrupt when MR0 matches the value in Timer

// Counter (TC).

// MR3S: [0] = Does not stop Timer Counter (TC) if MR3 matches Timer Counter

// (TC)

// MR3R: [1] = Resets Timer Counter (TC) if MR3 matches its value.

// MR3I: [0] = No interrupt when MR3 matches the value in Timer

// Counter (TC).

CTIMER1->MCR |= CTIMER_MCR_MR3R(1);

Plus the fact that PWM mode of operation is selected for channels 2 and 3:

// Configure match outputs as PWM outputs.

CTIMER1->PWMC |= CTIMER_PWMC_PWMEN3(1) | CTIMER_PWMC_PWMEN2(1);

The pin P3_12 must be configured for muxing slot alternative 4 as follows:

// Enable modules and leave others unchanged

// PORT3: [1] = Peripheral clock is enabled

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_CC1_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_CC1_PORT3(1);

// Release modules from reset and leave others unchanged

// PORT3: [1] = Peripheral is released from reset

MRCC0->MRCC_GLB_RST1_SET = MRCC_MRCC_GLB_RST1_PORT3(1);

// Configure P3_12

// LK : [1] = Locks this PCR

// INV: [0] = Does not invert

// IBE: [0] = Disables

// MUX: [0100] = Alternative 4 (CT1_MAT2)

// DSE: [0] = low drive strength is configured on the corresponding pin,

// if the pin is configured as a digital output

// ODE: [0] = Disables

// SRE: [0] = Fast

// PE: [0] = Disables

// PS: [0] = n.a.

PORT3->PCR[12] = PORT_PCR_LK(1) | PORT_PCR_MUX(4);

And finally, the timer is enabled:

// CEN: [1] = Enables the counters.

CTIMER1->TCR |= CTIMER_TCR_CEN(1);

The theoretical result is depicted in the following timing diagram:

FYI: the RGB LEDs are on when the pin is logic 0.

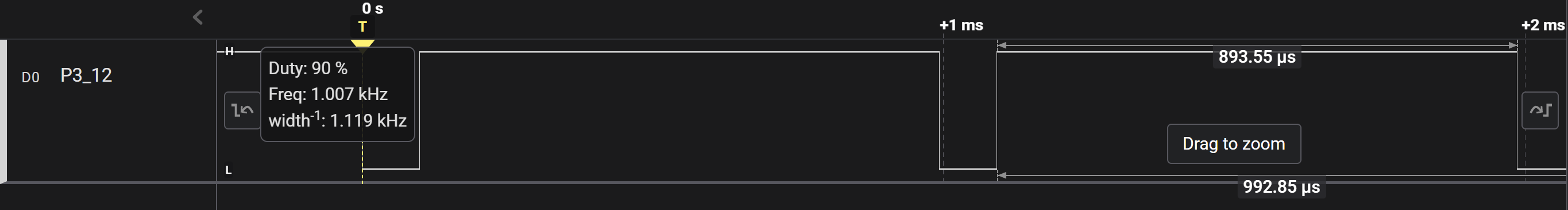

Checking the actual generated signal with a logic analyzer:

One thing to notice is that the CTIMER always generates inverted PWM signal (active low PWM)! In the example above this is not a problem, because the LEDs are on with logic 0. There is no configuration option to invert the generated PWM signal.

Assignment

Q1 In the example, the red LED was chosen and not the blue or green LED for a specific reason. Can you figure out that reason? Tip: look at the alternative functions of the pins.