C to assembly

Resources: ese_general_examples\advanced\c_to_assembly

Goal

To know the programmers model of the ARM Cortex-M processor. To know what a machine instruction is and know how to read several simple instructions written in assembly. To know the memory regions and what decisions a compiler makes when assigning a variable to a memory region. To know what the AAPCS is and what it tells about passing arguments and the return value of functions. Use type and class qualifiers to instruct the compiler to treat declarations different from default.

Cortex-M architecture

An ARM Cortex-M microcontroller is a machine that can be programmed to execute instructions. These instructions are often located in ROM memory, but can also be located in RAM.

Example machine instruction are:

- the addition of two numbers (ADD)

- the multiplication of two numbers (MUL)

- comparing two numbers (CMP)

- bitwise and-ing two numbers (AND)

- bitwise inverting a number (MVN)

- etc.

Two main architectures exist for the implementation of such machines:

- Load/store architecture, where machine instructions can access core registers only. This means:

- Load data into the core

- Process the data within the core

- Store the data back in memory or register

- Register/memory architecture, where machine instructions can access both memory and core registers.

ARM Cortex-M microcontrollers are load/store architectures.

Machine instructions

The MCXA153 microcontroller features an ARM Cortex-M33 CPU. This CPU is based on the Armv8-M architecture. The supported instructions by this machine are described in the Armv8-M Architecture Reference Manual.

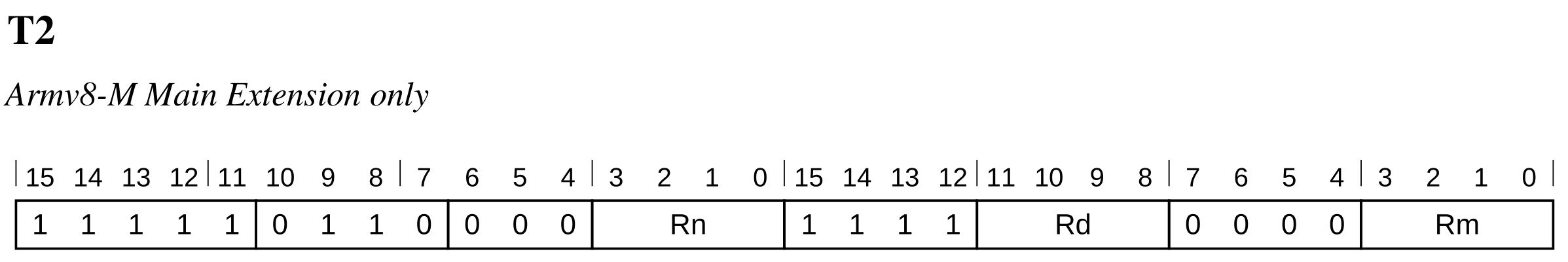

An example is the MUL instruction. The reference manual shows that it is implemented by two variants, called T1 and T2. T1 is a 16-bit instruction and T2 is a 32-bit instruction. The description shows how the instruction translates to 1's and 0's that will be stored in memory. However, for several bit-fields the 1's and 0's depend on the selected register:

- Rn: source register in the core. n is is a three or four bit value, depending on the variant.

- Rm: source register in the core. m is is a three or four bit value, depending on the variant.

- Rd: destination register in the core. d is is a three or four bit value, depending on the variant.

Programmers model

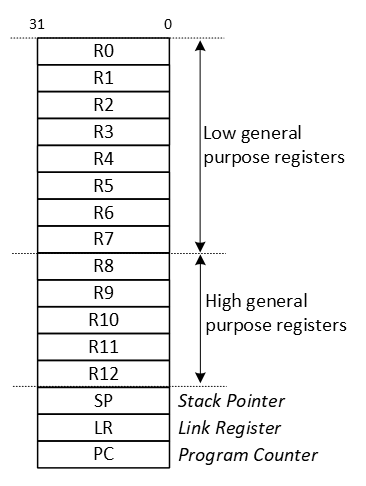

The available core registers are described in Armv8-M Architecture Reference Manual. This is known as the programmers model and depicted in the following overview:

As shown, there are sixteen 32-bit core registers.

Let's take a closer look at variant T2 of the MUL instruction:

Now, given de following instruction:

MUL R7, R0, R1

In this instruction:

- Rd=R7

- Rn=R0

- Rm=R1

This will yield the following instruction that will be stored in memory:

Rn Rd Rm

| 11111 | 0110 | 000 | 0000 | 1111 | 0111 | 0000 | 0001 |

This is equal to 0xFB00F701 in hexadecimal.

Conclusion: the core registers are used as sources and destination for the machine instructions. Machine instructions and their operands need to be loaded into the CPU before execution, hence the load/store architecture.

Assembly

Instead of having to write such binary or hexadecimal codes, the assembly language was developed. The general form of an instruction written in assembly is:

<operation> <operand1> <operand2> <operand3>

There may be fewer operands. The first operand typically is the destination register, the others are source registers.

As an example, the multiplication instruction as mentioned above in assembly is:

MUL R7, R0, R1

An assembler is a tool that is normally installed as part of the IDE and translates assembly instructions to machine instructions. Assembly instructions are often located in .s files or in inline assembly directly in .c files. An example of inline assembly is

for(uint32_t i=0; i<1000; i++)

{

// NOP is the No Operation instruction. It has no operands and is used to wait one CPU clock cycle.

__asm("nop");

}

Special registers

As can be seen in the programmers model, several special registers exist. These are the program counter (PC), the link register (LR), and the stack pointer (SP). The purpose of these registers is explained in more detail later, after taking a look at the memories that are available in the microcontroller.

Memories

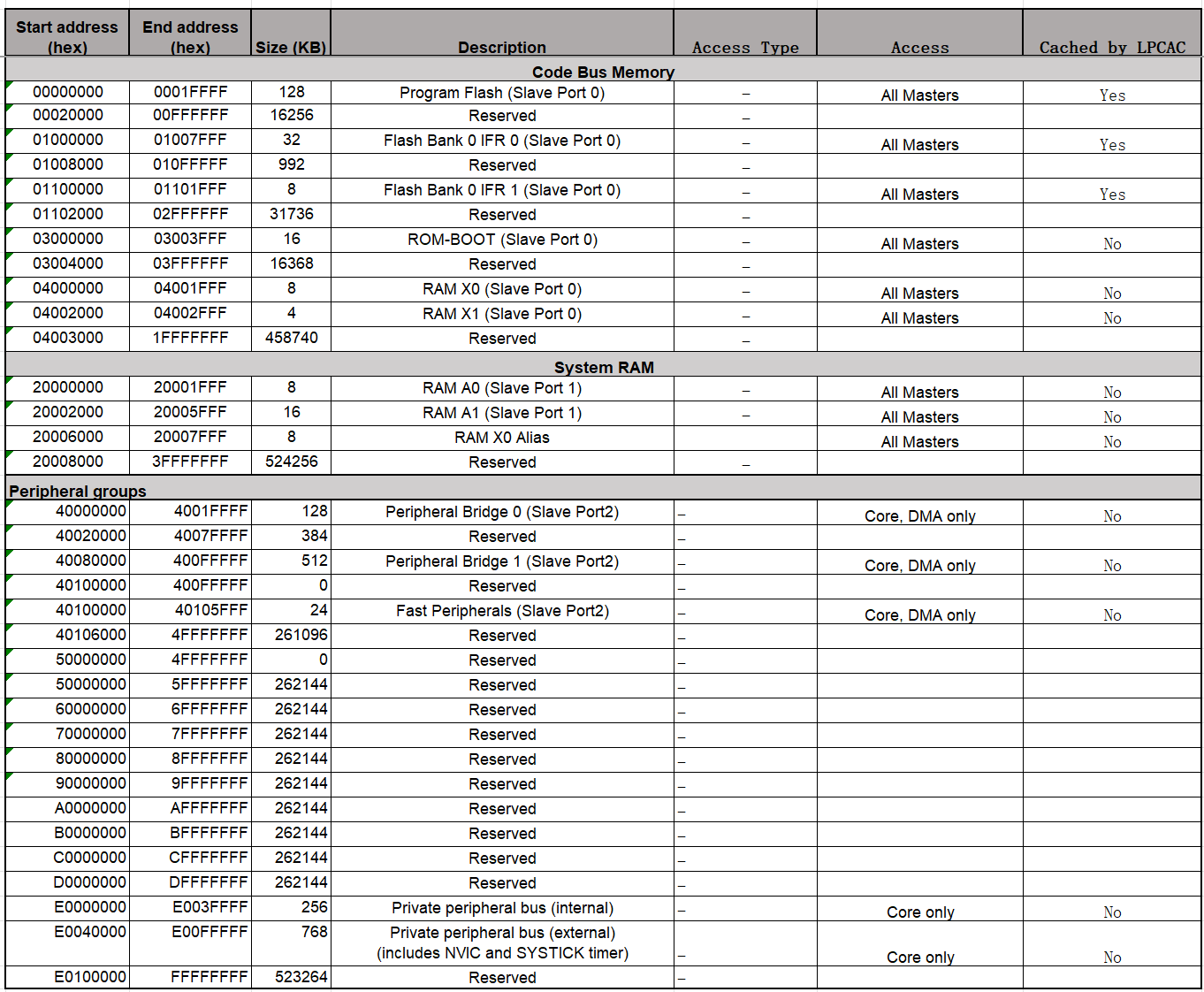

An ARM Cortex-M microcontroller features a 32-bit memory map. This means that 2^32 = 4 GB of bytes can be addressed. The memory map of the MCXA153 microcontroller is as follows:

The memory map shows which addresses are in use to access flash, RAM, peripheral registers and core registers.

The available RAM memory, which is 32 kB (8 + 16 + 8, starting from address 0x20000000) for the MCXA153, is used in three ways:

-

For static R/W data

These variables exist from program start to program end and are typically global variables. Static in this context means a static memory address, not a static value.

-

For automatic R/W data

These variables exist from function start to function end and are typically variables declared within a function. Automatic in this context means that the memory address is assigned during runtime. It is unknown at compile time. The memory region called stack is used for this purpose, which will be explained in more detail later.

-

For temporary R/W data

These variables exist from explicit allocation to explicit deallocation. This is done with functions such as malloc() and free(). The allocated memory remains allocated, even when a function returns. The memory region called heap is used for this purpose, which will be explained in more detail later.

Why these different options? Most often, the amount of RAM in a microcontroller is limited. So compilers try to reuse the available RAM us much as possible.

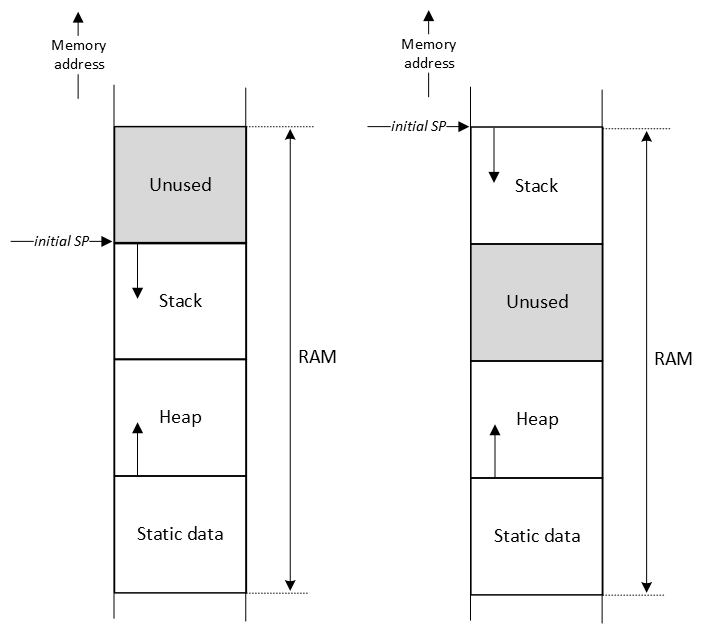

The following image shows two typical RAM layouts. The image was inspired by this blog.

The size of the Static data region is known at compile time. The size of the Heap and Stack regions are configurable in the IDE, for example in a scatter (.sct) file. If malloc() is not used in the application, the heap size can be set to zero. All microcontroller applications use a stack. To determine the size of the stack of you application, this blog is a must read. Notice that library functions, such as printf(), and interrupt handlers, also use the stack.

The stack is a LIFO data structure to temporarily store data. The top of the stack is recorded by the stack pointer (SP in programmers model). As can be seen in the image, in a Cortex-M microcontroller, the stack grows from a high memory address to a low memory address. If the size of the stack is not managed properly, chances are that other regions are overwritten when the stack increases. There is no hardware mechanism that checks, for example, that the SP is equal to an address that is used for the heap region.

As mentioned, the stack is used to store automatic variables. In addition, the stack is also used for storing other 'housekeeping' data, such as the value of core registers. If a function is called, and in this function register R7 must be used, the content of R7 can be saved on the stack at the start of the function, R7 can be used for the duration of the function, and at the end of the function, the value can be restored. This is achieved by using the PUSH and POP operations as follows:

multiply: // 'multiply' is called a label. It is translated into a

// memory address by the linker. This memory address,

// holds the first instruction of this function (entry

// point).

0x00000214 B480 PUSH {R7} // R7 is used in this function, but it's value should be

// restored after this function is done. Therefore, save it

// on the stack.

0x00000216 FB00F701 MUL R7,R0,R1 // Multiply R0 and R1 and store the result in R7.

0x0000021A 4638 MOV R0,R7 // R0 should contain the multiplied result, so move it.

0x0000021C BC80 POP {R7} // Restore the value of R7

0x0000021E 4770 BX LR // Return from function

The example above shows in the first column the address where the instruction is stored in memory and in the second column the instruction in hexadecimal notation. The address of the instruction that will be executed next by the CPU is stored in the program counter (PC in programmers model). After the instruction is executed, the PC is automatically increased by the size of the instruction (2 or 4 bytes).

In case a function is executed, the CPU needs to remember where it came from. In other words, what is the address of the next instruction? This address is stored in the link register (LR in programmers model) and used when returning from a function as shown in the last instruction in the example above. It simply means that the PC will get the value of the LR and operation continues where it left off.

As there is a single LR in the CPU core, you might wonder what happens with the LR if inside a function another function is called? In that case, the LR will first be stored on the stack and at the end of the function be restored.

Type and class qualifiers

The C programming language contains keywords that can be used to tell the compiler to treat declarations different from default.

-

const

These variables are only read and not written. They can be located in ROM instead of RAM.

const char *str = "This string is located in ROM memory\n";

-

static

These variables are always assigned a fixed memory address and will be placed in the static memory region. Even when declared in a function. An advantage of this is the fact that the value is not reset between function invocations and the scope of the variable is that particular function.

static uint32_t global_cnt = 0;

void pulse_counter(void)

{

// This variable is newly created on the stack each time this function is called

uint32_t local_cnt = 0;

// This variable is created one time in static data section

static uint32_t static_cnt = 0;

// What is the value of these variables when this functions has been called 10 times?

local_cnt++;

static_cnt++;

global_cnt++;

}

-

volatile

These variables can change outside normal program flow and should never be optimized by the compiler. Examples are variables shared between main and an ISR. Or peripheral registers. Not being optimized means that the compiler should implement a load-store operation for each access to this variable, instead of keeping a copy in a core register.

static volatile bool switch_pressed_flag = false;

Q1 Given the following example application. For each variable:

- Will it be located in RAM or ROM?

- If in RAM, will it be located in the stack, heap, or static region?

int var01 = 0;

unsigned char var02 = 0;

char var03[32] = {0};

static int var04 = 0;

static unsigned char var05 = 0;

static char var06[32] = {0};

volatile int var07 = 0;

volatile unsigned char var08 = 0;

volatile char var09[32] = {0};

const int var10 = 0;

const unsigned char var11 = 0;

const char var12[32] = {0};

int func(int a, int b)

{

int var13 = 0;

unsigned char var14 = 0;

char var15[32] = {0};

static int var16 = 0;

static unsigned char var17 = 0;

static char var18[32] = {0};

volatile int var19 = 0;

volatile unsigned char var20 = 0;

volatile char var21[32] = {0};

const int var22 = 0;

const unsigned char var23 = 0;

const char var24[32] = {0};

return a + b;

}

int main(void)

{

int var25 = 0;

unsigned char var26 = 0;

char var27[32] = {0};

static int var28 = 0;

static unsigned char var29 = 0;

static char var30[32] = {0};

volatile int var31 = 0;

volatile unsigned char var32 = 0;

volatile char var33[32] = {0};

const int var34 = 0;

const unsigned char var35 = 0;

const char var36[32] = {0};

var25 = func(1,2);

while(1)

{}

}

AAPCS

One important topic not discussed so far is the way arguments are passed to and from functions. One can think of several options, such as the stack, the core registers, or a dedicated section of the static RAM. In order to standardize these options, ARM came up with the Procedure Call Standard for Arm Architecture AAPCS.

For passing arguments, the following basic rules apply:

- Process arguments in order they appear in source code

- Round size up to a multiple of four bytes

- Use core registers R0 to R3, align doubles to even registers

- Use stack for remaining arguments, align doubles to even addresses

- Call the function (LR is saved and PC gets the value of the first instruction of that function)

For returning a value from a function, the following basic rules apply:

-

Returning a fundamental data type (e.g. int, char, pointer, etc.)

- 1-4 bytes: R0

- 8 bytes: R0-R1

- 16 bytes: R0-R3

-

Returning a composite data types

- 1-4 bytes: R0

- all other sizes: stack

If the stack is used, the caller function allocates space for the return value and passes the pointer to that space to the function.

Notice that the core registers are preferred, because this is faster when compared to the stack.

Compiler differences

Compilers are used to translate C code into machine instructions. Although code is generated for the same machine, you should assume that different compilers will generate different instructions. This is even true when using another version of the same compiler. Or when changing compiler settings, such as optimization.

Two compilers that are often used for ARM Cortex-M processors are ArmClang and GCC. To provide a basic idea of the differences, the generated machine instructions generated for the function sum() is compared. The function is implemented and called as follows:

int32_t sum(int32_t a, int32_t b)

{

return a + b;

}

int main(void)

{

int32_t s = 0;

int32_t m = 0;

s = sum(1, 2);

m = mul(1, 2);

while(1)

{}

}

- Compiler: AC6 (ArmClang V6.21) - Optimization: -O0

67: { // As per AAPCS: arguments a and b are in R0 and R1

0x00000590 B082 SUB sp,sp,#8 // Creates space for 8 bytes (for 2 32-bit registers) on the stack

0x00000592 9001 STR r0,[sp,#4] // Store argument a on the stack, 4 address relative from the SP

0x00000594 9100 STR r1,[sp,#0] // Store argument b on the stack, 0 address relative from the SP

68: return a + b;

0x00000596 9801 LDR r0,[sp,#4] // Load argument a from the stack in R0, 4 address relative from the SP

0x00000598 9900 LDR r1,[sp,#0] // Load argument b from the stack in R1, 0 address relative from the SP

0x0000059A 4408 ADD r0,r0,r1 // Execute operation: R0 = R0 + R1. Result in R0 as per AAPCS

0x0000059C B002 ADD sp,sp,#8 // Restore stack space for 8 bytes

0x0000059E 4770 BX lr // Branch to where the application came from

- Compiler: GCC (Arm GNU Toolchain 12.2.Rel1 (Build arm-12.24)) 12.2.1 20221205 - Optimization: -O0

67 { // As per AAPCS: arguments a and b are in R0 and R1

sum:

00004a6e: push {r7} // Save R7 on the stack

00004a70: sub sp, #12 // Creates space for 12 bytes (for 3 32-bit registers) on the stack

00004a72: add r7, sp, #0 // Save the value of SP in R7

00004a74: str r0, [r7, #4] // Store argument a on the stack, 4 address relative from R7

00004a76: str r1, [r7, #0] // Store argument b on the stack, 0 address relative from R7

68 return a + b;

00004a78: ldr r2, [r7, #4] // Load argument a from the stack in R2, 4 address relative from R7

00004a7a: ldr r3, [r7, #0] // Load argument b from the stack in R3, 0 address relative from R7

00004a7c: add r3, r2 // Execute operation: R3 = R3 + R2

69 }

00004a7e: mov r0, r3 // Move the value in R3 to R0 as per AAPCS

00004a80: adds r7, #12 // Calculate restored stack space for 12 bytes

00004a82: mov sp, r7 // Restore stack space

00004a84: pop {r7} // Restore R7

00004a86: bx lr // Branch to where the application came from

- Compiler: AC6 (ArmClang V6.21) - Optimization: -O3

The function is never called, because the result is not used in main.

- Compiler: GCC (Arm GNU Toolchain 12.2.Rel1 (Build arm-12.24)) 12.2.1 20221205 - Optimization: -O3

The function is never called, because the result is not used in main.

From a functional point of view, the two compilers with the same settings produce code that behaves exactly the same. They both calculate the sum of the two numbers in R0 and R1 and return the result in R0. The machine instructions to produce this result are, however, quite different.

Q2 Why is there no need to store the LR on the stack in the sum() function?

Example - Extra

The following application starts in the function main(). Instead of the C instructions, the assembly instructions are given in the first column. For each instruction, the updated value of several registers is presented after the instruction is executed. Examine the table and make sure you understand why a particular value is assigned to a register.

Note. This example is created with:

- Compiler: AC6 (ArmClang V6.21) - Optimization: -O0

- Debugger: Keil MDK-ARM

| Executed instruction | PC | LR | SP | R1 | R0 | Note |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0x00000588 | 0x00000527 | 0x20005FF0 | 0x40091824 | 0x00000589 | Initial situation when main is started | |

| PUSH | 0x0000058A | 0x20005FE8 | R7 and LR are pushed on the stack, so the SP decrements by 8-bytes | |||

| SUB sp,sp,#0x18 | 0x0000058C | 0x20005FD0 | Space for 24 (0x18) more bytes allocated on the stack | |||

| MOVS r0,#0 | 0x0000058E | 0x00000000 | Move the value 0 into R0 (# means immediate) | |||

| STR r0,[sp,#8] | 0x00000590 | Store the value in R0 8 places relative from the SP | ||||

| STR r0,[sp,#0x14] | 0x00000592 | Store the value in R0 20 places relative from the SP | ||||

| STR r0,[sp,#0x10] | 0x00000594 | Store the value in R0 16 places relative from the SP | ||||

| MOVS r0,#1 | 0x00000596 | 0x00000001 | Move the value 1 into R0 | |||

| STR r1,[sp,#4] | 0x00000598 | Store the value in R1 4 places relative from the SP | ||||

| MOVS r1,#2 | 0x0000059A | 0x00000002 | Move the value 2 into R1 | |||

| STR r1,[sp,#0] | 0x0000059C | Store the value in R1 0 places relative from the SP | ||||

| BL sum (0x000005E0) | 0x000005E0 | 0x000005A1 | Branch to sum() function. The PC is set to the address of the first instruction of sum(). The LR is set to the address of the next instruction in main | |||

| SUB sp,sp,8 | 0x000005E2 | 0x20005FC8 | Space for 8 more bytes allocated on the stack | |||

| STR r0,[sp,#4] | 0x000005E4 | Store the value in R0 4 places relative from the SP | ||||

| STR r1,[sp,#0] | 0x000005E6 | Store the value in R1 0 places relative from the SP | ||||

| LDR r0,[sp,#4] | 0x000005E8 | Load the value in R0 that is located 4 places relative from the SP | ||||

| LDR r1,[sp,#0] | 0x000005EA | Load the value in R1 that is located 0 places relative from the SP | ||||

| ADD r0,r0,r1 | 0x000005EC | 0x00000003 | R0 = R0 + R1 | |||

| ADD sp,sp,#8 | 0x000005EE | 0x20005FD0 | Space for 8 bytes restored from the stack | |||

| BX lr | 0x000005A0 | Branch to the address saved in the LR | ||||

| STR r0,[sp,#0x14] | 0x000005A2 | Store the value in R0 20 places relative from the SP | ||||

| Etc. |

Assignment

Q3 What is the purpose of the PC?

Q4 What is the purpose of the LR?

Q5 What is the purpose of the SP?

Given the following function prototype:

int func(int a, int b);

Q6 According the AAPCS, how are the arguments a and b passed?

Q7 And also according AAPCS, how is the value returned?

Q8 What is the purpose of the PUSH and POP instructions?

Q9 Is an automatic variable stored in the stack, heap or static data?

Q10 Why is it called an automatic variable?

Given the following declaration of a global variable:

static int var = 0;

Q11 What does static in this context mean?

Q12 What is the heap?

Q13 What is the purpose of the type qualifier const?

Q14 In a Cortex-M application, how is the size of the static data, stack and heap managed?

Given the following code example:

typedef struct

{

uint32_t level;

char name[36];

} test_t;

void func1(test_t test);

void func2(test_t *test);

Q15 What is the difference in terms of memory usage for func1() and func2()?